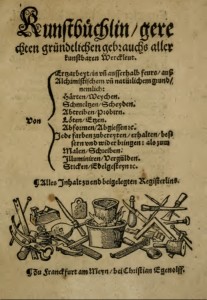

In 1535, the German printer Christian Egenolff, who had recently set up shop in Frankfurt, published a 45-page booklet titled Kunstbüchlein (Little Book of Skills). This rough little pamphlet, cheaply printed on coarse paper just in time to be offered for sale at the Frankfurt Book Fair that year, would hardly seem a likely candidate to spark a revolution. But, in many ways, it did just that: Not a scientific revolution, but a revolution in how people thought about a science that had long been regarded—for good reason—with suspicion and distrust.

In 1535, the German printer Christian Egenolff, who had recently set up shop in Frankfurt, published a 45-page booklet titled Kunstbüchlein (Little Book of Skills). This rough little pamphlet, cheaply printed on coarse paper just in time to be offered for sale at the Frankfurt Book Fair that year, would hardly seem a likely candidate to spark a revolution. But, in many ways, it did just that: Not a scientific revolution, but a revolution in how people thought about a science that had long been regarded—for good reason—with suspicion and distrust.

When we think of alchemy, we usually associate the word with an esoteric, quasi-mystical but deluded search for deep secrets; or, alternatively, with fraudulent get-rich-quick schemes. Of course, both were part of the world of Renaissance alchemy—which explains why Pope John XXII issued a papal bull in 1317 condemning the art. But alchemy was just as likely to have had a strictly practical, utilitarian orientation. And that is the course steered by Egenolff’s little booklet. Read more »