In an earlier post, I discussed the source of the Renaissance charlatan’s power and suggested that charisma—that difficult to pin down, divinely endowed quality that inspires devotion and awe in others—was the secret of the charlatan’s ability to manipulate an audience and attract buyers for his nostrums.

The sociologist Max Weber defined charisma as “a certain quality of an individual personality by virtue of which he is set apart from ordinary men and treated as endowed with supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional powers or qualities.” Weber, who believed that charisma was key to leadership, also observed that charisma is in the eyes of the beholder: “charisma can only be that which is recognized by believers as charismatic.” In other words, it is a leader’s followers—not, of course, a divinity—that “endow” an individual with charisma.

The personal magic that arouses special devotion or loyalty or enthusiasm for a public figure is always conveyed through performance. The charlatan—whether a politician or a purveyor of medical nostrums—is a showman, and his practice is always a form of theatre.No wonder charisma is so difficult to pin down. Though hard to explain, it can be pictured—and, in fact, was brilliantly depicted in the late Renaissance. The power and charisma of the charlatan is vividly captured a painting by the 17th century Sienese artist Bernardino Mei (1612-1676).

The picture, painted in 1656 and titled Il Ciarlatano (The Charlatan), depicts an aged, bearded charlatan seated on a wooden platform and surrounded by an astonished and wondering crowd of onlookers. The scene takes place in the Piazza del Campo in Siena—the Torre del Mangia is clearly visible in the background. As was customary for charlatans (ciarlatani), the rickety wooden stage has been hastily erected in the piazza for the day. The portly man wears an unkempt beard and is dressed in old clothes stained with the chemicals of the workshop where he concocts his mysterious nostrums. A filthy robe with a blue sash, white leggings and heavy black shoes complete his rough costume.

The view of the charlatan from below accentuates his imposing figure, while the dark, foreboding sky above heightens the drama of the scene. The floor of the stage is littered with an assortment of glass bottles and vials containing his remedies. Next to the healer’s cane is a handbill bearing the title, L’Olio de’ filosofi di Straccione (Straccione’s Philosophers’ Oil), identifying the charlatan and extolling the virtues of his remedy.

The drama of the scene is heightened as Straccione suddenly lifts, precariously balanced on the back of his tightly fisted hand, a vial of his miraculous elixir and thrusts it toward the crowd, while pumping the air with his other fist as he praises the remedy’s power. Straccione’s penetrating gaze and authoritative gestures arouse expressions of wonder and fear in the crowd below, which listens in rapt attention as the charlatan proclaims that its very health and well-being is contained in the powerful contents of that little vial. The onlookers look up to Straccione almost as if he were Christ offering the key to salvation.

As a portrait, the picture is not flattering: Drawing upon conventions of genre paintings, Mei portrays the tired, aging charlatan Straccione (or Ragamuffin) as a mixture of Old Testament prophet and tattered alchemical philosopher. Yet, with the oversize charlatan towering above a wondering crowd, the picture conveys the traditional connection between healing rituals and dramatic performances—for that is how shamans operate.

It’s not easy to tell how much of Straccione’s patter was ritual, how much it involved local healing traditions, and how much was plain ballyhoo. Apparently the quasi-religious elements of folk medicine were gradually becoming commercialized and transformed into advertising gimmicks. In the Renaissance charlatan, the folk healer emerges as a commercialized shaman.

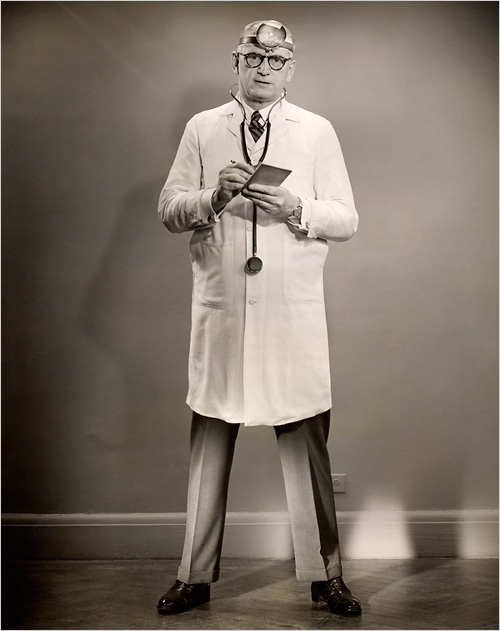

The Renaissance charlatan’s charisma contrasts sharply with the serious, scientific demeanor of the modern doctor. In modern medicine, the physician’s costume (white coat and stethoscope hanging around the neck), manner (grave or optimistic), and language (medical terminology) are all meaningful and can affect the outcome of a therapeutic encounter—but they pale in significance to the dramatic, imposing presence of Bernardino Mei’s charlatan.

The physician in George Marks’s 1950s era photograph is an officious, bureaucratic, and rational doctor. Pen and notebook in hand, stethoscope reassuringly dangling from his neck, and head mirror at the ready for diagnostic examination, he gazes with a serious, “scientific” look. Whereas Straccione is deliberately scary—warning that disease is a serious and unpredictable thing—Marks’s doctor, with his clean white lab coat and scientific paraphernalia, is reassuring. You can trust this doctor.

In the popular imagination, the white lab coat that Marks’s doctor wears is as much a part of the modern doctor’s persona as a cowboy’s 10-gallon hat. A 2004 study found that 56 percent of patients surveyed felt that physicians should wear them. About 94 percent of U.S. medical schools have “white coat ceremonies” in which new students don the garment to signify their entry into the profession.

However, these days lab coats seem to be disappearing. Despite their powerful cultural history, the doctor’s white coat may be on its way out. The authority they once connoted has been supplanted by anxiety. The term “white coat syndrome” or “white coat hypertension” is now commonly used to explain the nervousness that many patients feel upon seeing their doctor. “There’s been a trend toward taking the coats off in the last 20 years because they were felt to be intimidating,” reports physician and medical historian Guenter Risse. “In this mechanistic and impersonal age of medicine we’re living in, some doctors have felt they could establish a better relationship in their street clothes.”

Besides, it turns out that the physician’s lab coat is not as squeaky clean as its whiteness is supposed to convey. A 2009 New York Times story reported that the American Medical Association is considering a policy that would require doctors to hang up their white coats—for good. The concern comes from studies that show that lab coats can harbor dangerous bacteria and transfer it from one patient to another. To make matters worse, other studies show that the majority of medical personnel at some hospitals say they change their lab coats less than once a week.

Despite the medical profession’s concerns, plenty of doctors still cling to their white coats. As one doctor surveyed by the Times said, “Are we going to go around naked?”

Imagine that: Your doctor in the examination room standing stark naked before you. A stethoscope dangles from his neck, bumping against his hairy chest. Your eyes wander because you can’t help it. “So how are we feeling today?” asks your bare-naked but well scrubbed, bacteria-free doctor.

With a scene like that, you might prefer Straccione—ragamuffin clothing and all.

References:

Bernardino Mei’s picture is now displayed in the Banca Monte dei Paschi in Siena, where visitors can view it in a well-lit space along with the bank’s other artistic treasures. For further discussion of the painting, see David Gentilcore, Medical Charlatanism in Early Modern Italy (Cambridge, 2006). Further discussion of the charlatan as a “commercialized shaman” may be found in Peter Burke, “Rituals of Healing in Early Modern Italy,” in The Historical Anthropology of Early Modern Italy: Essays on Perception and Communication (Cambridge, 1987), pp. 207-20. Max Weber’s discussion of charisma occurs first in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (trans. N. Eisenstadt, 1930) and his generated a huge critical literature.