How do charlatans operate? What is the source of their fascination—and their power?

Charisma, of course. But what is the source of that charisma? I think that two things are important: First, the claim to possess “secret knowledge”; and second, the claim to have discovered the single cause (or causes) of all diseases.

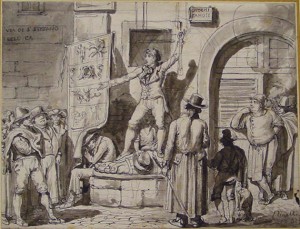

Two examples will serve to illustrate this. One is of a young medical student of the first century A.D. by the name of Thessalos of Tralles. The other is the 16th-century surgeon Leonardo Fioravanti, who is the subject of my book, The Professor of Secrets: Mystery, Medicine and Alchemy in Renaissance Italy (National Geographic, 2010).

We know Thessalos by an autobiographical letter he wrote to the Roman Emperor Claudius. The epistle forms the the preface to a treatise on astrological medicine attributed to the Egyptian pharoah Nechepso.

Thessalos writes that after studying philosophy in Asia Minor, he set out for Alexandria, the cultural capital of the Hellenistic world, to study medicine. One day, while scouring the shelves of the Library of Alexandria, he discovered King Nechepso’s treatise describing how to collect, prepare, and administer medicinal plants according to their appropriate astrological signs.

Eager to discover Nechepso’s secret of the universal panacea, Thessalos followed the book’s instructions to the letter. Alas, his every attempt failed. In despair, the young student decided to seek a divine revelation. His search took him to Thebes, where he located a priest skilled in the art of theurgy (invoking visions of dieties to obtain oracles from them). Thessalos pursuaded the sorcerer to summon before him Asclepius, the god of medicine, so that he might ask the god, “face to face,” the secret of making Nechepso’s healing drugs.

On the appointed day, the priest led Thessalos into a darkened chamber, recited a magical incantation, and conjured before the student a vision of the god in a bowl of water. Thessalos had come prepared: unknown to the priest, he brought papyrus and ink to record the god’s revelation.

“Oh blessed Thessalos, today a god honors you,” proclaimed the apparition. “Soon, when they have learned of your success, men will hold you in reverence as a god! Ask me what you please, and I will gladly answer you in all matters.”

“I could scarcely speak,” reported the young student, “so much was I taken outside myself and so fascinated was I by the god’s beauty. Nevertheless, I asked why I had failed in trying out Nechepso’s recipes.” The god replied:

King Nechepso, though a very intelligent man and in possession of all magical powers, had not received from any divine voice the secrets you want to know. Endowed with a natural cunning, he understood the affinities of stones and plants with the stars. However, he did not know the proper times and places where the plants must be gathered. Now, the growth and withering of all fruits of the season depends upon the influx of the stars. Furthermore the divine spirit, which in its extreme subtlety can pass through all substances, is poured out in particular abundance in the places successively touched by astral influences in the course of cosmic revolution.

The god then revealed the secret of collecting the plants, the astrological signs that govern them, and the prayers that must be recited when gathering them, without which the drugs have no power. Having revealed the mystery, the god commanded Thessalos not to “reveal [the secret] to any profane person who is a stranger to our art.”

Not long after these events took place, Thessalos went to Rome to seek his fortune. Pliny reported that Thessalos was one of a host of ambitious charlatans who preyed upon the credulous Romans, who were all too easily duped by the novel medical fads coming in from the East. “We are swept along on the puffs (flatu) of the clever brains of Greece,” lamented Pliny. Arriving in Rome during the Principate of Nero, Thessalos made a fortune with his new‑fangled doctrine. He denounced the theories of Hippocrates and proclaimed that all diseases could be reduced to but three “states” of the human body. The essence of Methodism, the school Thessalos founded, is the principle that all medical doctrines are false; there are only individual diseases.

According to Pliny, Thessalos “swept away all received doctrines, and preached against the physicians of every age with a sort of rabid frenzy.” He attracted many pupils, promising to teach them everything there was to know about medicine in only six months. Evidently the god’s promise of fame came true, for Pliny reports that when Thessalos walked the streets of Rome he was surrounded by a greater crowd than any actor or charioteer. His monument on the Appian Way bore the inscription, iatronices, “conquerer of the physicians.”

My other example, the Bolognese surgeon Leonardo Fioravanti, made similar claims. Although it is debatable whether Fioravanti was a charlatan, he certainly made extravagant claims for his cures, which he said were the “secrets” he discovered not from a god but from old empirics and soldiers from the South of Italy. It was in Sicily, he wrote, that he discovered the lost secret of the “first physicians,” who didn’t know any kind of scientific medicine, but just had “good judgment.”

The secret? That all diseases stemmed from a single cause, the “corruption” of the body that began in the stomach. The cure, then, took the form of a variety of “panaceas,” especially the Great Medicine, which purged the body of pollution and returned it to a state of “pristine health.”

Like Thessalos, Fioravanti went on to become a celebrity, touting his “new way of healing” and promising miracles.

Of course, there are important differences between Thessalos of Tralles and Leonardo Fioravanti. Whereas Fioravanti advertised his “secrets” as having stood the test of experience, Thessalos offered the proof of divine revelation for his, experience having failed him.

How do you tell a charlatan from a “true doctor?” Certainly not by the diploma on the wall. Thessalos was a doctor, too, having studied with distinguished Greek physicians. Fioravanti had a medical degree from Bologna, one of Renaissance Italy’s best medical schools.

And not by success or failure, either: I’ve had chiropractors who cured me and physicians who failed. A friend of mine swears by her acupuncturist, though her doctor warns against him. Fioravanti offered countless testimonials attesting to the efficacy of his cures.

And finally, not by pedigree. In defending the ancient ways of the “first physicians” against the purveyors of “false medicine,” Fioravanti could trace his back to the original discoverers of medicine who, he said, had been persecuted and abused by the regular doctors. The physicians may have called him a charlatan, but, he was quick to respond, the real quacks were those “with little practice and a whiff of Galen.”