Surgery is no art for the squeamish. A simple slice through the skin – the practiced surgeon’s daily experience – may be enough to give an ordinary person nausea.

The history of surgery is replete with instances of daring surgical interventions, harrowing battles against blood-gushing wounds, amputations accomplished at lightning speed and without anesthesia, amazing successes as well as spectacular failures. If it takes a certain amount of daring to be a surgeon, with or without anesthesia, it also takes practice, and the learning curve can be a steep one.

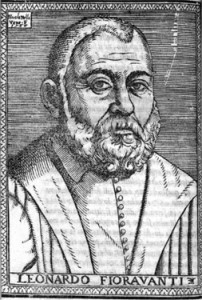

My book, The Professor of Secrets: Mystery, Medicine and Alchemy in Renaissance Italy, tells the story of one novice surgeon’s learning curve on the way to becoming an expert surgeon. Leonardo Fioravanti, the book’s protagonist, practiced his art at a time when surgeons did not go to medical school, but instead learned their art as did other craftsmen: by watching and imitating a master.

Leonardo, an eager and observant apprentice, was dissatisfied with what he had learned in his native Bologna. So he journeyed to Sicily, where it was said that surgeons accomplished remarkable things. There, he learned the art of alchemy, which he used to perfect unguents to heal wounds. An old pharmacist showed him diapalma, a rare salve for treating the sores caused by syphilis made from the plant zaffaioni, which grows only on Mount Pellegrino near Palermo. Another old empiric taught Leonardo ways to treat wounds that were completely new to him. The man was able not only to heal patients, “but to almost raise them from the dead.” As he gathered knowledge, his reputation as a surgeon grew. Before long, people were calling him “the New Asclepius.”

Emboldened, he would take on any case brought to him, no matter how risky—even those that the physicians had “given up as dead.” In April 1549, a captain in the Spanish navy by the name of Matteo Greco came to visit Leonardo. His 24-year-old wife, Marulla—said to be the most beautiful woman in the city—was desperately ill. Some months back, Captain Greco recounted, Marulla had come down with a “malignant fever” that had swollen her spleen and “caused both of her legs to become horribly ulcerated,” leaving her utterly debilitated. Several physicians had examined Marulla and told her the spleen would have to be removed. The operation was not dangerous, they assured her—though as Fioravanti matter-of-factly notes, “none of them would do it.”

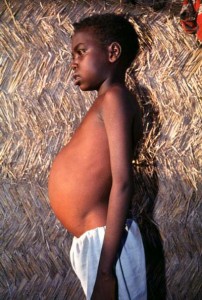

In modern medical terms, Marulla had splenomegaly (also megalosplenia), or “big spleen disease.” It is characterized by massive swelling of the spleen and sharp pain in the abdomen. The spleen can grow to enormous proportions—as much as 80 times its normal size—grotesquely distending the abdominal region. The most common cause of splenomegaly is malaria, endemic to southern Italy and Sicily in Fioravanti’s day. Splenomegaly is easily treated with antimalarial drugs. Left untreated, however, it can be a dangerous disease. Rapid enlargement of the spleen may result in splenic rupture, and massive splenomegaly can place a heavy burden on the heart and circulatory system. Whereas a normal spleen absorbs only 5 percent of the heart’s blood output, an enlarged spleen may absorb more than half. In addition, splenomegaly often causes an increase in the volume of blood plasma, which may result in anemia. It can also cause sharp pain in the abdomen and back, especially if the spleen has become so large that it puts pressure on other organs. That was evidently the case with poor Marulla. She was in such pain, Leonardo writes, that “she finally decided that she would either be cured or would die.” Marulla begged her husband to find a surgeon who could perform the recommended operation.

Aware of Fioravanti’s reputation, Captain Matteo asked the surgeon if he had the courage to take out her spleen. Leonardo picks up the story:

“Why, yes,” I answered cheerfully, even though up until that time I’d never done anything like it. To tell the truth, even though I promised him I’d do it, I really didn’t want to because I was afraid I might botch it. But I knew an old surgeon from the town of Palo in the Kingdom of Naples. He was called Andreano Zacarello and he operated with the knife, removing cataracts and similar things, and was very expert in that profession. So I called for the old man and he hurried to my house. I asked him, “Dear Master Andriano, a strange wish has come to Captain Matteo’s wife: by Hercules, she wants to have her spleen taken out! Tell me, can this be done safely?”

“Of course,” the old man answered. “I’ve done it many times.”

“Do you have the courage to go ahead with it now?” He said that he’d do it with me, but otherwise not. So we agreed to do it together.

I went back to arrange things with the woman and her husband, then went to the authorities to give her up as dead, according to the custom. With this license, we went back one morning to the woman’s house. We laid her on a table and had two servants hold her fast. Then the good old surgeon took out a razor and cut the woman’s body just above the spleen, which popped out of her body like a fishing float. We quickly separated the organ from the tissue until we had it completely out, then sewed up the wound, leaving a tiny air-hole. I treated the wound with hypericon oil, powder of incense, mastic, and myrrh with sarcocolla, and made her drink water boiled with a dried apple, betony, and cardo santo. I took care of her in this way until, in just twenty-four days, she was completely healed. She went to mass at the Madonna of the Miracles, according to her obligation, and was healed and saved.

Having accomplished the unimaginable, Fioravanti created an amazing publicity stunt to advertize his surgical talents. He carried the deformed organ to the open-air merchants’ arcade (loggia de’ mercanti), where it was displayed for three days. Marulla’s spleen, weighing fully two pounds (the organ normally averages only about five ounces), was a marvelous sight to behold. As people passed by to view it, Leonardo must have told and retold the story of the extraordinary surgery, embroidering it with each iteration until it became a mythical tale of medical heroism. “The glory of this experiment was mine,” he gloated, “and because of this the people gathered about me, as to an oracle.”

Marulla Greco was lucky. She survived the operation and lived for several years. But the chances of failure were extremely high for such a procedure. The operation could have turned out very differently.

Every surgeon is aware that every case is in some way unique, and that the art of surgery is perfected only through practice. As the surgeon an author Atul Gawande writes in his book, Complications, “The moral burden of practicing on people is always with us, but for the most part unspoken.” Just as in the art of playing the violin, the one thing that separates a good surgeon from the less accomplished one is the amount of practice put in. Patients, on the other hand, want perfection without a learning curve. What nobody wants to admit is that the two are contradictory desires.

To readers wanting to learn more about the limitations of surgery, I recommend Atul Gawande, Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2002.)