The Renaissance was an era of new diseases. Between 1347 and 1600, Western Europe was struck by a succession of new and baffling epidemics. Not only did Europe experience its most devastating demographic upheaval as a result of the rapid, epidemic spread of the Black Death (presumably bubonic plague), it was struck by a succession of new infectious diseases, including typhus, syphilis, virulent smallpox, and the mysterious “English sweat,” which first broke out in 1485.

In the Renaissance—at least until the foundation of public health boards in the 16th century—the struggle against epidemic diseases was waged principally by the religious orders. Most of the charitable hospitals that cared for victims of the epidemics were founded by religious orders; many orders devoted themselves specifically or even exclusively to treating victims of the new epidemics.

One such order was the Jesuati, a little known religious order founded in 1360 by Giovanni Colombini (c. 1300-1367), a wealthy Sienese merchant who gave away all his possessions in order to live as a mendicant. The Jesuati—not to be confused with the more famous Jesuit Order—were originally called the Clerici apostolici Sancti Hieronymi, (Apostolic Clerics of St. Jerome) because of their special veneration of St. Jerome; but Colombini and his disciples soon gained the name Jesuati—supposedly from the habit of loudly crying “Praise be to Jesus Christ” at the beginning and end of their sermons. (So the Jesuati were roughly the equivalent of “Jesus freaks.”)

From its origins, the Jesuati Order dedicated itself to caring for victims of the plague. They established hospitals, visited the sick, and dispensed charity to the poor. But what makes the Jesuati stand out among other religious orders is that, besides providing health care to the poor, they specialized in making distilled “elixirs” and cordials, which they believed preserved the body from corruption and putrefaction. Hence the Jesuati acquired a new name among the populace: the Aquavitae Brothers, from aqua vitae (water of life), the highly alcoholic medicinal waters that they manufactured and distributed to the people.

The medical doctrine that underlay this practice was inspired by the writings of the 14th century Franciscan friar John of Rupescissa, who taught that spirit of wine (alcohol) was the incorruptible “fifth essence” of substances: It is related to the four qualities as heaven is related to the four elements. Following John’s lead, the Jesuati set up distilleries throughout Italy and manufactured remedies, which they distributed gratis to the poor. Even if aqua vitae did not cure the plague, it may have enabled its inebriated victims to better tolerate their suffering.

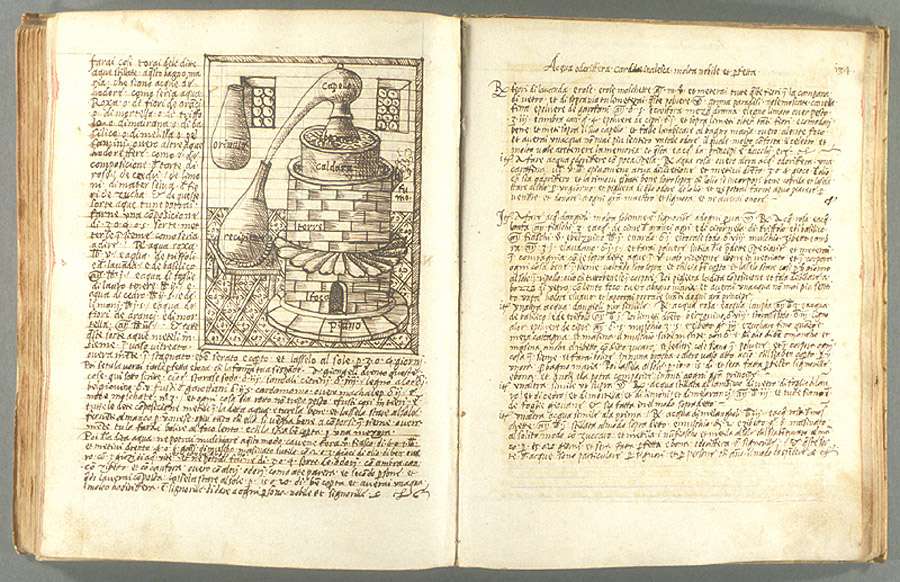

The only work that has survived relating to Jesuati alchemy is a sixteenth-century Libro de i secretti e ricette composed by one of the order’s brothers, Giovanni Andrea di Farre de Brescia. (The manuscript, now in the Spencer Research Library at the University of Kansas, is labeled Pryce MS E1.) Composed between 1536 and 1562, the manuscript is lavishly illustrated with figures of distillation apparatus and contains detailed descriptions of distillation procedures. It enumerates hundreds of remedies for ailments affecting all parts of the body. Much is devoted to mal francese (syphilis), and there are repeated references to guaiac wood (lignum vitae), a famous drug from the New World. The page opened below displays an illustration of a brick alchemical furnace with an alembic for distillation resting on top.

And there is more. The brothers who compiled this beautiful manuscript offered many more secrets, including recipes for distilled waters to soothe and cleanse sore eyes, waters of sage, fennel, and other odiferous herbs, prayers to cure headaches, and “A miraculous method to conserve health for a long time.” Some of the recipes are blotted out, perhaps suggesting experiments that didn’t work.

The Jesuati order spread to cities throughout Italy in the 16th century, where they set up convents with alchemical laboratories and manufactured aquavitae to distribute to the poor.

Besides alchemical experiments, the order produced some distinguished mathematicians, including Bonaventura Cavalieri, a disciple of Galileo and professor of mathematics at Bologna who wrote works on optics, geometry, astronomy. Cavalieri’s pupil Stephano degli Angeli was also a member of the order. Angeli, who became a professor of mathematics at the University of Padua, wrote treatises on geometry cosmology, mechanics, and physics—including a dialogue on the two systems of Ptolemy and Copernicus in the Galilean style.

The Jesuati Order was disbanded in 1668 by Pope Clement IX, possibly because of abuses connected with the manufacture and distribution of alcoholic beverages. The female branch of the order, the Jesuati sisters, founded by Colombini’s cousin Caterina Colombini (d. 1387) in Siena, survived in small communities in Italy until 1872.

The Jesuati deserve to be better known. Renaissance doctors had no cure for the plague, or for any of the other diseases that afflicted people. Of course, neither did the Jesuati have a cure. But at least they could provide a medicine that eased the suffering of the debilitating and often fatal diseases that ravaged Europe during the Renaissance.

To learn more about the Jesuati:

Kennedy, T. (1910). Blessed John Colombini. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Dear Bill,

Things like this make me love History. What amazing post!

Please, we need a paper on this topic from you right now. Or a book!

Ever,

Miguel