“Is there no balm in Gilead? Is there no physician there?” (Jeremiah 8:22)

Jeremiah’s plaintive words express the fundamental lament of the human heart: In times of tragedy and sadness, where is God in this moment? Has He abandoned us?

While in the passage from Jeremiah the Balm of Gilead is used as a metaphor about the human search for understanding and meaning in the face of difficult circumstances, the Balm of Gilead was in fact real; and the quest for a medicine that will heal all wounds is itself as old as Jeremiah.

The Balm of Gilead is generally thought to refer to Mecca balsam, the resinous gum of Commiphora gileadensis (C. opobalsamum), a small tree native to southern Arabia but also naturalized in ancient Judea. Mecca balsam was prized both as a perfume and a balm to treat wounds. Modern studies have confirmed that C. gileadensis possesses antibacterial properties that validate its usage in the local treatment of wound infections.

The search for wound-healing balms was seemingly endless. Magical waters and balms are common motifs in medieval folklore, and the ancient dream of a magical balm that healed wounds instantly without leaving a scar was still alive in the Renaissance. Cervantes turned it into a good joke with Don Quijote’s “Fierabrás’s balm,” two drops of which will heal a knight cut in half.

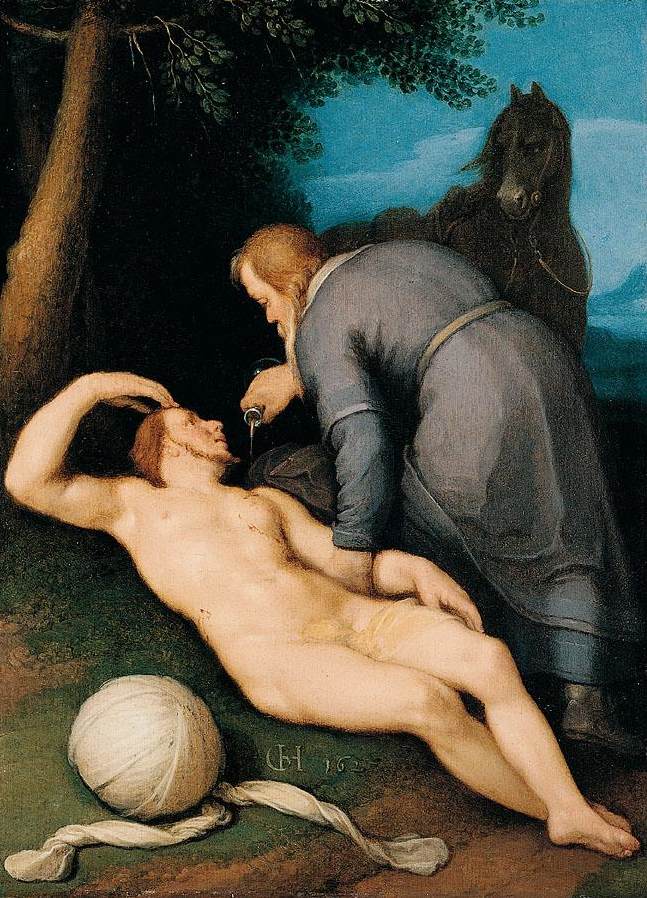

No surprise, then, that wound balms turn up fairly frequently in the period’s art. One of the more common motifs in which wound treatments were present was the parable of the Good Samaritan, the story of the traveler on his way to Jericho who is assaulted by robbers and left for dead, then saved by a Samaritan who chances upon him lying in the road and nurses his wounds.

Among the many representations of the parable that show the Samaritan using a wound healing balm, I reproduce two here. The first, by the Dutch painter Cornelis van Haarlem (1562-1638), depicts the Good Samaritan leaning over the wounded traveler and consoling the distraught man. Holding a vial of liquid in his hand, the Samaritan pours the balm into the wound.

In the other picture, by the Neapolitan painter Luca Giordano (1634-1705), the Good Samaritan holds a jar of balm in one hand and gently anoints the traveler’s wound with a cloth dipped in the medicine.

Depictions of the story of the healing of St. Sebastian by St. Irene—a particularly popular theme during the baroque period—also display wound balms. According to the story, the Roman emperor Diocletian commanded that Sebastian, a Christian convert, be tied to a stake and shot with arrows. Miraculously, though riddled with arrows “like a hedgehog” and left for dead, Sebastian survived. A widow, Irene of Rome, went to retrieve his body in order to bury it, and found him still alive. Irene brought him back to her house and nursed him back to health.

In one of countless late-Renaissance depictions of the story—a painting by the 17th century Milanese artist Francesco Cairo (1607-1665)—St. Irene holds a vial of medicine in one hand and applies the ointment to the wound with a brush or feather.

In another painting, by the Spanish artist Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652), Irene’s assistant holds a bottle of balm, while the saint daubs the medicine on Sebastian’s wound.

A painting by the French artist Nicolas Régnier (1590-1667) depicts a similar scene. In this picture, Irene’s assistant holds a jar of balm, while Irene dips her hand into balm and applies it to the wound on Sebastian’s leg.

Medieval and Renaissance military surgeons continued to experiment with wound balms, and their “books of secrets” are jam-packed with recipes for them. Renaissance artists, who read books of secrets for their pigment recipes, would have known about the balms, and might even have seen surgeons employing them.

Did these “marvelous” balms really work? Evidence suggests that they did. One of the most famous military surgeons of the Renaissance was Leonardo Fioravanti, who claimed to have invented a “new way of healing” battle wounds. His secret? It consisted of three wound balms that he discovered experimentally. As was typical of Fioravanti (a notorious self-promoter), he gave them catchy trade names: Mighty Elixir, Blessed Oil, and Leonardo’s Grand Liquor. All were made by distilling mixtures of herbs containing tormentil, hypericum (St. John’s Wort), and alcohol. Tormentil and hypericum have long been used successfully as styptics and both contain antibacterial agents, while alcohol gave the balsams antiseptic properties.

Renaissance wound balms, though loaded with folklore—weren’t just figments of the imagination. They worked.

One of the more bizarre Renaissance wound balms was one described by the French surgeon Ambrose Paré. In his Apology and Treatise, he described an ointment to treat gunshot wounds that he claimed was the secret of a famous Piemontese surgeon. (See Holly Tucker’s excellent post.) This grotesque balsam, called “oil of whelps,” was made by boiling live puppies with earthworms, oil of lilies, turpentine, and aqua vitae. His balm—for which he evidently received great credit in the French court—was (by his own admission) a formula he obtained from a “famous” Piemontese surgeon.

Paré was a notorious liar and thief (see my post, “The Legend of Ambrose Paré“). In fact, the recipe for his prized balm was almost exactly the same as one for “oil of a red dog” described in the famous book of secrets of “Alexis of Piedmont” (I Secreti del reverendo donno Alessio Piemontese, 1555). Did Paré obtain his recipe from Alessio’s book and make up the story about convincing the surgeon to give him the secret? It wouldn’t be his first fabrication.

It is now known that wound healing is a complex process. While modern surgeons better understand how wounds heal, except for the huge strides made in the treatment of chronic wounds we do not treat wounds very much differently today than when Fioravanti practiced: suture the wound, apply an antiseptic agent, and let nature take its course.

The dream of discovering a miraculous wound-healing balm is one of humankind’s most enduring and hopeful myths. The dream lives on.

The dream of discovering a miraculous wound-healing balm is one of humankind’s most enduring and hopeful myths. The dream lives on.

Meanwhile, for just ten bucks you can buy a jar of Balm of Gilead—or, at any rate, something called “Balm of Gilead Herbal Salve”—from The Common Sense Farm.

Make more discoveries about wound healing balms from these works:

William Eamon, The Professor of Secrets: Mystery, Medicine, and Alchemy in Renaissance Italy (2010)

Thank you for this well written, comprehensive and informative article.

In Ireland, in my youth living in the remote countrside, farmers used honey mixed with alcohol to treat burns, cuts and small wounds. It worked.

One small correction. Saint Sebastian was “riddled with arrows” but not like an “urchin” The reference comes from a compendium of lives of the Saints, written about 1260, called the “Golden Legend”, which relates that the saint was “shot with arrows until he looked like a hedgehog” (Latin “ericius”)

Thank you for this correction. The nice thing about a blog is that corrections can be made simply and I’m glad to make this one. I’m glad you liked the post. Honey has long been used as a topical treatment for wounds; but you may be interested in knowing that recent studies confirm the antibacterial activity of honey, which researchers now attribute to the defensin-1 protein, part of the bee’s immune system. Empiricism works!