[Note: In my seminar on “The Scientific Revolution” this semester, I assigned graduate students to write a blog post that, once revised by the class during a workshop, I would publish on my “Labyrinth of Nature” blog. It was an exceptionally useful writing assignment because it helped the students identify an interesting problem or topic and to write an engaging piece about the subject for a general audience. I am pleased to post the first of these pieces, by Master’s history student James Sherwood.]

Early modern doctors had a variety of different ways to heal the many diseases that afflicted the population. Although most adhered to the teachings of the ancient physician Galen, others followed the Swiss medical reformer Paracelsus and practiced the new, chemical mode of healing. Doctors sometimes used methods based on occult sciences for diseases that they judged to be occult. Plague was once such illness. A disease of the whole body, plague resulted from hidden, or occult, causes that could not be adequately explained in conventional, Galenist terms. As a result, some doctors turned to occult remedies.

In 1641, Thomas Sherwood, a London “practitioner in Physick,” wrote a book of cures for the plague titled The Charitable Pestmaster. Among his many ways to cure and fend off the plague was “the puppy cure.” The cure was especially useful for the old and weak, Sherwood explained:

In 1641, Thomas Sherwood, a London “practitioner in Physick,” wrote a book of cures for the plague titled The Charitable Pestmaster. Among his many ways to cure and fend off the plague was “the puppy cure.” The cure was especially useful for the old and weak, Sherwood explained:

If any that are ancient or weak shall be infected with the pestilence, it shall not be necessary to give them any purge, vomit, or sweat, or to let them bleed; because they cannot bare the loss of so many spirits as are spent by such evacuations. Therefore you may lay upon the pit of the stomach of the sick a young live puppy, and if the sick can but sleep the space of three or four hours, they shall recover presently, and the dog shall die of the plague. This I have known approved; and I do believe that it will be a cure for all lean, spare, and weak bodies both young and old: provided, that the dog be younger then the sick.

Sherwood’s cure, which he claims he has “known and approved” by experience, is based on the occult principles of sympathy and antipathy. According to this doctrine, everything in the universe has a relationship of sympathy and antipathy to other objects. Thus the puppy has a sympathetic relationship to the plague, and for that reason draws out the corruption of the pestilence from the body of the sick into the body of the puppy. The poor puppy becomes the victim of the plague and the sick patient lives.

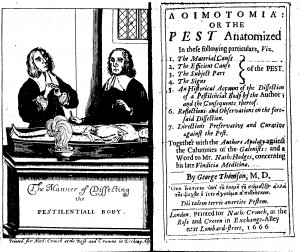

Related to this cure is one performed in 1665 by chemical physician George Thomson. During the great plague of London, Thomson relates, he performed an anatomy of a plague victim and, as a result of the anatomy, found himself the victim of the plague. He tried to cure himself using his own chemical remedies—taking more than he would give his patients—but to no avail. In desperation, he turned to a method that was in common use during this plague—although much debated by physicians: the “toad cure.”

Thomson took a dried toad, which he himself carefully prepared “in as exquisite manner as possible,” and wrapped it in a linen cloth. He then put the toad on his stomach and left it for a few hours. To his astonishment, the dried toad swelled up “to the bigness that it was an object of wonder.” Thomson relates he would not have believed it if he himself had not seen it. From this Thomson deduced the healing wonder of the dried toad and used the example to argue its utility to other doctors. This cure is also based on the doctrine of sympathy and antipathy. As Thomson explained, the dried toad “doth draw the pestilential poison so into its body.” The toad attracts the plague to itself and swells up to a “marvelous” size, leaving the victim free of the plague.

Thomson took a dried toad, which he himself carefully prepared “in as exquisite manner as possible,” and wrapped it in a linen cloth. He then put the toad on his stomach and left it for a few hours. To his astonishment, the dried toad swelled up “to the bigness that it was an object of wonder.” Thomson relates he would not have believed it if he himself had not seen it. From this Thomson deduced the healing wonder of the dried toad and used the example to argue its utility to other doctors. This cure is also based on the doctrine of sympathy and antipathy. As Thomson explained, the dried toad “doth draw the pestilential poison so into its body.” The toad attracts the plague to itself and swells up to a “marvelous” size, leaving the victim free of the plague.

The “toad cure” and the “puppy cure” both used the doctrine of occult qualities that was popular during early modern times. Thomson named Paracelsus as the founder of the “toad cure.” Paracelsus, who taught the principles of sympathy and antipathy, argued that like heals like and that natural objects have a sympathetic link to one another. Thomson was a follower of the Paracelsian physician Jan Baptist van Helmont. Praising van Helmont, Thomson wrote, “Van Helmont, who shines with such a bright lustier in his orb, that the Galenical bats and owls are not able to look him in the face.” Thomson used his experiment to prove the efficacy of Paracelsian and Helmontian cures. One wonders: Did he really perform the toad cure or was it just a polemical way to strike at the Galenists?

The toad and puppy cures supposedly worked sympathetically to attract the plague out of the victim and into the animals themselves. Such cures were deduced for diseases whose causes were occult. The plague and its cures were insensible and were hidden in nature, hence occult. Surprisingly, because they were supposedly based on experiment, cures such as the toad and puppy cures were more likely to be performed by the supporters of the new philosophy of medicine, who advocated an experimental approach to medicine.

Cunning folk, wise women, and witches were not the only ones engaged in magical healing. Early modern physicians also used practices stemming from occult traditions in their treatments.

By James Sherwood (MA candidate, history)

Works Cited

Sherwood, Thomas. The Charitable Pestmaster or the Cure of the Plague. London, 1641.

Thomson, George. Galeno-pale or a Chymical Trial. London, 1665.

George Thomson, Λοιμοτομια: Or The Pest Anatomized. London, 1665.

Very interesting reading!

Great topic and presentation of facts. I learned something I am not sure I really wanted to know.