In the Renaissance, diseases frequently took on terrifying aspects. They were dangerous enemies, never to be taken lightly. Even familiar diseases such as leprosy and plague were feared adversaries that had to be combated with every means at hand. Besides such familiar sicknesses, early modern Europe was besieged by a host of new and mysterious diseases such as syphilis and typhus, for which doctors offered scant hope for a cure. Diseases were formidable adversaries that required martial cures.

Enter alchemy, the science of transmutation and perfection, with its promise of providing healers with an arsenal of powerful remedies to combat the diseases that loomed and terrorized. Wildly popular and hugely controversial in the 16th century, alchemical drugs—from potable gold to herbal quintessences—gave healers new ammunition to combat the diseases of the time.

What exactly did alchemical drugs do that made them so appealing to early modern healers? For one thing, alchemists purported to produce a more “pure” form of conventional medicines by distillation and other means. Distillation enabled alchemists to extract the pure “quintessence” of things, leaving the material dross behind.

In addition, alchemists claimed, one could also produce more powerful drugs using alchemical techniques. One of the most common therapeutic actions alchemists aimed at in producing their remedies was purgation—cleansing the body of the “corruptions” that caused sickness.

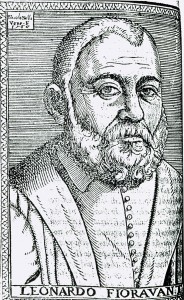

The 16th century Italian surgeon and alchemist Leonardo Fioravanti took full advantage of the growing demand for alchemical cures. Fioravanti touted a “new way of healing,” which, he claimed, far outdid the weak and ineffectual methods of the regular physicians. Experience had convinced him that robust purges and emetics to rid the body of toxic matter were more efficacious than the physicians’ diets and regimens.

The most prominent feature of Fioravanti’s therapeutics is the frequency with which he recommended violent purgations. He was obsessively concerned with purifying the body of corrupting substances, which he believed were the cause of all illness. He had an imposing armory of emetics and purgatives—all made alchemically—whose active agents included hellebore, antimony, and mercury. He gave them catchy trade-names such as Angelic Electuary and Magistral Syrup. However, of all the alchemical medicines that Fioravanti experimented on, “Precipitato” (mercuric oxide, HgO), was the one he trusted the most. Its marvelous properties were the core of his “new way of healing.”

Alchemically produced, Precipitato was a “modern” panacea that imitated the virtues of the herbal remedies that Fioravanti witnessed people using to purge themselves in imitation of the “natural way” of healing. It was a potent drug that, in Leonardo’s words, “is used in cases of festering pains to take out the corrupt matter from the interior parts to the exterior”—in other words, a robust purge that would cleanse the interior of the body and return the body to its pristine natural state.

Precipitato was a strong drug, alright. Like other mercury salts, mercuric oxide is extremely toxic. A deadly poison, it is in small doses a powerful emetic. Fioravanti would have had to use the drug with extreme caution. His usual dosage—ten to twelve grains dissolved in rosewater—would have resulted in a highly toxic formula if the entire amount were ingested.

However, mercuric oxide is only slightly soluble in water; hence, if Fioravanti administered a dosage comprised of the solution alone (leaving the undissolved solids behind), he would have administered a much more dilute form of the drug. The “solution in rosewater” that he prescribed to patients would have resulted in a strong but probably not fatal purge. Even so, on more than one occasion Leonardo was accused of killing his patients with his potent drugs. Prescribing Precipitato was playing with fire.

Fioravanti’s obsessive concern with purgation was hardly unique. It was a therapeutic approach advocated by many popular healers of the day. Zefiriele Tommaso Bovio (1521-1609), a Verona empiric, championed purging with a fervor that equalled if it did not surpass that of Fioravanti. Bovio, who attacked the orthodox physicians in books with titles like Scourge of the Rational Physicians and Thunderbolt Against the Supposed Rational Doctors, claimed that the doctors killed their patients with their strict diets and weak medicines. Like Fioravanti, he preferred strong emetics and purges. He especially recommended his “Hercules,” which he reported made one of his patients “vomit a catarrh as big as a goose’s liver, and emit loathsome excrement from above and below.”

Others urged similar practices. Pietro Castelli (c. 1570-1661), the author of an authoritative treatise on purging, Emetica (1611), chastised therapists “who indulge and yield to an illness.” Weak medicines only mollify the sickness, he wrote, “but do not drive it out completely.” Castelli’s emetic of choice was white hellebore (Veratrum album), an extremely toxic herb, which he advocated because “The illness and therefore the medicament should be strong; for strength leads to victory.”

According to the conception of disease favored by many popular healers, illness was not some benign imbalance of humors that could be rectified by diet and regimen. It was an invasion of the body by corruptions that had to be forcefully expelled with potent drugs. In the struggle between sickness and health that these popular healers waged, therapeutic intervention necessarily took on heroic dimensions.

The conception of disease as a contamination of the body resonated with the tense political and religious climate of post-Tridentine Italy. Historians have observed that the golden age of the witch-hunts coincided with an age of super-purges, of ostentatious cleansings of the sullied flesh, and of obsession with individual catharsis and collective purification. Moreover, the use of exorcisms peaked during the period of the Catholic Counter-Reformation. Exorcisms—often publicly performed—demonstrated in a dramatic fashion the Church’s jurisdiction over supernatural forces, making them effective instruments of anti-Protestant propaganda.

Woodcut illustrating an exorcism being performed on a woman by a priest and his assistant, with a demon emerging from the woman’s mouth. (From Pierre Boaistuau, Histoires prodigieuses et memorables, Paris, 1598)

Since the line between demonic possession and diseases of natural origin was difficult to draw in the 16th century, exorcists and physicians competed with one another over contesting jurisdictions. The resulting ambiguity of professional roles and identities made it possible for popular healers to appropriate the role of exorcist—and for exorcists to play the role of the doctor. Thus hellebore, a powerful purging drug that Fioravanti and Bovio frequently used, was a staple agent to drive out demons. Franciscan friar Girolamo Menghi, whose Flagellum daemonum (“Scourge of Demons”) was a standard manual to instruct exorcists, praised its virtues. Menghi reported having seen all manner of maleficent objects emitted by the body during exorcisms by way of vomiting and purging. He also noted that some exorcists abused the art by indulging in carnevalesque, self-aggrandizing displays of power over demons. In that world, where it was often impossible to tell whether diseases were of natural or demonic origin, the figure of the exorcist and the charlatan merged.

I do not think it is going too far to suggest that in cleansing the stomach and driving out its polluting sickness, Leonardo Fioravanti was performing a kind of physiological exorcism. His treatments, acts of purification, mimicked the exorcist’s rite of “chasing away demons from tormented bodies.” Rarely did Fioravanti merely heal his patients; he always “healed and saved” them.

Fioravanti’s martial therapeutic style—widely imitated by marginalized healers—eventually won out and became the dominant ideology of modern medicine. Of course, neither Precipitato nor any of his other wonder drugs became medicine’s “magic bullet,” and the idea of bodily pollution as the universal origin of disease would be discarded. Instead, the 19th-century discovery that infectious diseases were caused by specific pathogens—and that they could be cured by specific drug therapies—pointed the way to modern medicine. The germ theory of disease, first formulated microbiologist Louis Pasteur, ushered in a dramatic “therapeutic revolution,” forever changing the way we treat and think about diseases. Yet the similarities between Fioravanti’s mode of therapy and the modern therapeutic model are unmistakeable. Like the modern doctor, he insisted that the only rational therapy must be aimed at the agent causing the disease. And, he thought, it was possible to find a counter-agent that could eradicate that cause and expel it from the body.

In today’s medicine, curing has replaced caring as the dominant ideology of modern, technology-driven medicine. Fioravanti had the same ambition, but his dream did not come true for more than two centuries. Ironically, as chronic illnesses became society’s most intractable medical problem, the military metaphor seems less compelling, and the model that Fioravanti fought so hard to defeat is becoming more relevant than ever.

REFERENCES:

Piero Camporesi, The Incorruptible Flesh: Bodily Mutation and Mortification in Religion and Folklore. Translated by Tania Croft-Murray (Cambridge, 1988).

William Eamon, The Professor of Secrets: Mystery, Medicine, and Alchemy in Renaissance Italy (Washington, 2010).

Great blog you’ve got here.. It’s difficult to find quality writing like yours nowadays.

I seriously appreciate people like you! Take care!!