“From the highest to the lowest, the people seem fond of sights and monsters.”— Oliver Goldsmith, 1762.

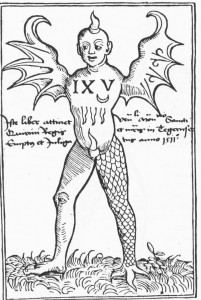

In March, 1512, two decades after Christopher Columbus set sail on the momentous voyage that would open up the New World to the European consciousness and seven years before Martin Luther pinned his ninety-five theses to Wittenberg’s cathedral door, thus plunging Europe into its deepest religious crisis since the foundation of Christianity, a Florentine pharmacist recorded in his diary that a “monster” had been born in Ravenna. The pharmacist, Luca Landucci, described the strange misbirth with these words:

It had a horn on its head, straight up like a sword, and instead of arms it had two wings like a bat’s, and at the height of the breasts it had a fio [Y-shaped mark] on one side and a cross on the other, and lower down at the waist, two serpents. It was a hermaphrodite, and on the right knee it had an eye, and its left foot was like an eagle’s.

Eighteen days later, Landucci reported that a coalition of papal, Spanish and French troops had sacked Ravenna. “It was evident what evil the monster had meant for them,” he concluded. “It seems as if some great misfortune always befalls the city where such things are born.” Rumors that the child was “born of a nun and a friar” fueled propaganda about corruption within the clergy, while others saw the monster as prefiguring great ills to befall all of Italy.

Since it appeared during the first century of the printing press, it’s not surprising that the Ravenna monster transmogrified into various popular images, all portentous and threatening. Pictures of the monster appeared in broadsheets and posters in Rome, Florence, Spain, and France. At each stop, the image accreted new and more portentous meanings. A version of the monster’s image appeared in a German broadsheet of 1512 (this time referring to a monstrous birth in Florence), and again in 1581—this time in an English pamphlet appropriately titled The Doome, warning all men to the Judgement.

Birth deformities, while not common, are well known in the medical literature. Although the modern medical term for such anomalies—teratism—still carries its Greek root “monster,” few educated people nowadays attribute anything monstrous or portentous to them. When they do occur, the modern sensibility dictates that the “normal” reaction should be one of sympathy for the parents and pity for the birth-defected child. As for the notion that teratisms or comets might be portents of coming disasters, such beliefs may still occasionally be the stuff of supermarket tabloids, but modern science rejects them outright as superstitions, holdovers from a bygone past.

The radically divergent interpretation of birth defects in the Renaissance versus in modern times is illustrative of the vast cultural chasm that separates our age from theirs. It’s not that sixteenth-century intellectuals lacked naturalistic explanations for such apparent anomalies: A long tradition of scholarly commentary on “monsters” made possible rational, scientific explanations for what Aristotle called “preternatural phenomena,” or events occurring outside the normal course of nature. Renaissance intellectuals marshaled their own scientific explanations to account for such unlikely events, just as moderns do.

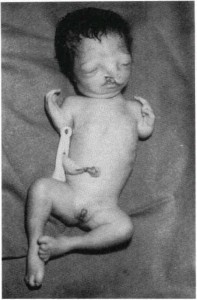

The “monsters,” of course, were real and had a purely human fate. Most died prematurely from natural causes, which was the fate of a deformed child born in 1514 in Bologna. She was the daughter of Domenico Malatendi, who raised vegetables outside the city. According to chroniclers who described the birth, the child had two faces, two mouths, three eyes, and no nose. On the top of her head she had an excrescence described as “like a red cockscomb” or “an open vulva.” The child was baptized in the cathedral of San Pietro on 9 January and christened Maria. She died four days later.

Though brief, little Maria’s life caused quite a stir. According to contemporaries, the Bolognese astrologers interpreted the infant as “a sign of great pestilence and war.” A Roman observer, having seen a printed illustration of the child, interpreted Maria’s body as a symbol of “calamity-stricken Italy, now so prostrated and lying with open vulva that many outsiders, whom we have seen before us, have come to luxuriate and run wild.” Similar expressions of alarm came from Venice and Florence.

Hardly anyone, it seems, wanted these infants to survive—so dire were the prophecies surrounding them. Some died as a result of deliberate withdrawal of care and nourishment. That is what happened to the Ravenna monster, which Pope Julius II ordered to be starved to death. The same fate befell a “monstrous” child born in Florence in 1506, which “by order of the Signoria was not fed and died.” Others were abandoned to hospitals or exposed and left to perish. Sometimes the “monsters” were embalmed and displayed, serving as gruesome reminders of God’s just wrath.

The interpretation of monsters as portents and objects of horror fed on local anxieties and circumstances of the moment. Thus the Italian wars fueled interest in prodigies in the years between 1594 and 1530, during the most destructive phase of the hostilities. In Germany, the religious struggles of the Reformation likewise generated intense concern with monsters and prodigies.

In the 1520s, monsters became staples of religious propaganda. A popular religious pamphlet by Martin Luther and Philip Melancthon contained illustrations (by Lucas Cranach) depicting two recent “monsters,” which Luther and Melanchton interpreted as prodigies and signs of divine wrath. According to the pamphlet, the “Pope-ass,” reportedly found dead in the Tiber River in 1496, referred to the monstrous corruptions of the clergy; while the “monk-calf” born in Freiburg with a mantle of skin resembling a cowl was interpreted as a sign that the monastic state was nothing more than a “lying appearance and outward display of a holy, godly life.”

Pope-ass and monk-calf. Martin Luther and Philip Melancthon, 'Deuttung der cwo grewlichen Figuren' (Wittenberg, 1523)

While most severely malformed infants perished within days or weeks of birth, a few did survive. Grotesquely, some were displayed in the marketplaces and piazzas for profit. Long objects of spectacle, monstrous children, though hardly wished for, presented parents with the prospect of showing them for money and enhancing their meager incomes. Landucci described such a case in his diary:

A Spaniard came to Florence, who had with him a boy of about thirteen, a kind of monstrosity, whom he went round showing everywhere, gaining much money. [The boy] had another creature coming out of his body, which had his head inside the boy’s body, with his legs and his genitals and part of his body hanging outside. [The boy] grew together with his smaller brother and urinated with him, and he did not seem greatly bothered by him. [qu. Daston/Park, Wonders, 190]

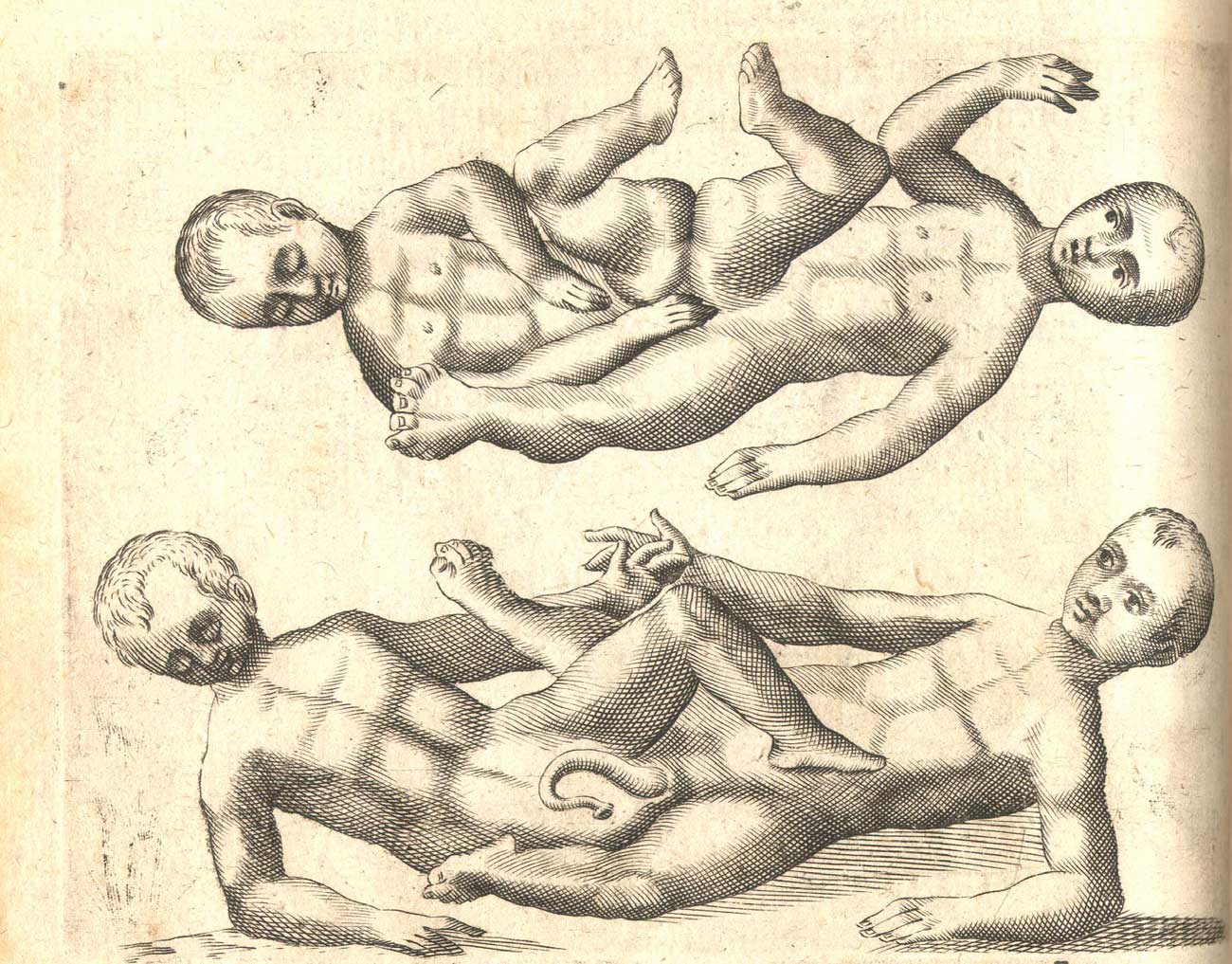

Horror, repugnance, and fear were not the only sentiments elicited by monstrous births. Paradoxically, early modern Europeans delighted in the display of monsters. In a popular 16th century treatise, Des monstres et prodiges (Of Monsters and Prodigies), the French surgeon Ambroise Paré depicted conjoined twins who were born in Verona around 1475. Paré reports that because their parents were poor, the twins “were carted around to several cities in Italy, in order to collect money from the people, who were burning to see this new spectacle.” Such displays were even licensed by city authorities.

Like the images of the Ravenna monster, Paré’s illustration of the conjoined twins had a long afterlife, appearing in numerous popular works on prodigies. The image gained its longest life through the ever-popular Aristotle’s master-piece. Originally published in 1684, this extremely popular work on generation and sexual reproduction was still being printed well into the 19th century. The book was a sort of “every person’s sex manual.” Amid tales of monstrous births owing to the mother witnessing traumatic events or having evil thoughts is a report on the female conjoined twins depicted here. Amazingly, the author claims, one twin outlived the other by three years, only to succumb from the burden of having to carry its sister’s corpse around with it!

The same goggle-eyed fascination with “monsters” that gripped Renaissance popular culture continued to be a part of medical science down through the 17th century. Fortunio Liceti, a professor of medicine at Padua, could hardly constrain himself when writing his authoritative Latin work on monsters, De monstrorum natura, caussis, et differentiis libri duo (On the nature, causes and differences of monsters), first published in 1616. Liceti’s monsters included many purely fabulous creatures, such as conjoined humans and animals, animals with human heads, and humans with animal parts. Yet amid this bizarre assortment of creatures were images of real birth anomalies, such as the conjoined twins pictured here. To Liceti, anomalies were examples of nature’s plasticity, not examples of God’s divine wrath.

Liceti’s history of monsters—with its strange mixture of the real and the fabulous—was tied to a Renaissance tradition that regarded monsters as “jokes” of nature. How very different was the view of his English contemporary, Sir Francis Bacon. With Bacon, the study of monsters became a doorway to the study of nature. Monsters, he wrote, illuminated nature’s regularities, for “he who has learnt her deviations will be able more accurately to describe her paths.”

In his Novum Organum (1620), the work in which he spelled out his program for a sweeping reform of philosophy, Bacon classified natural history as comprising three orders: that which “deals either with the Freedom of nature or with the Errors of nature or with the Bonds of nature.” In other words, nature could be studied as normal nature, aberrant nature, and nature manipulated by human artifice. In order to proceed with the second part of his program, Bacon wrote, “We must make a collection or particular natural history of all the monsters and prodigious products of nature, of every novelty, rarity or abnormality.” In this way, he thought, investigators would be led to an understanding of the causes of monsters.

Modern science has learned a lot about monsters. We now know that birth defects are caused by genetic mutations. We can be fairly certain that the Ravenna “monster” was an infant with Roberts syndrome, a deformity found in children who are born with an especially destructive mutation. The same could probably be said of many of the other “monsters” of the period, including little Maria Malatendi, the child born in 1514 that caused such a stir in Bologna.

The study of monsters is a constant reminder that science cannot only be about the human body as we wish it to be, but as it is—replete with variety and error. The “monsters” that so fascinated and frightened early modern Europeans are to modern researchers merely part of the vast spectrum of the human form.

How strange and distant, how barbaric, the world of the Ravenna monster seems to moderns. The fascination and fear of monsters that was characteristic of the Renaissance recalls St. Augustine’s fierce condemnation of curiosity. It was because of the “disease of curiosity,” wrote Augustine, that people gawk at monsters and freaks in theaters and circuses.

The passage from the Ravenna monster to the modern understanding of monsters was a long one. Modern science teaches us that mutations are everywhere. None of us escape them. Yet not all of us are equally subject to the force of genetic mutation. Some of us are born with many; others with comparatively few. Some mutations are benign, others destructive, and those that are destructive are usually driven out by natural selection. Yet we all carry them, a blunt fact that obscures the distinction between the normal and the aberrant.

We are all mutants; and in that sense, we all carry within ourselves and in our genes the capability of being and bearing monsters.

We are all the Ravenna monster.

REFERENCES

Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park, Wonders and the Order of Nature (New York, 1998)

Armand Marie Leroi, Mutants: On Genetic Variety and the Human Body (New York, 2003)

Ottavia Niccoli, Prophecy and the People in Renaissance Italy (Princeton, 1990)

Ambrose Paré, On Monsters and Marvels, trans. J. L. Pallister (Chicago, 1982)

“Wow, great article post.Thanks Again. Great.”

Came across this piece quite by accident. Good reading, it turned out: short and yet informative, historic and entirely engaging. Thank you.

–Signed—

— Another Ravenna Monster (perhaps Lady Gaga was more onto something that any of us thought, eh? Hmmm…..)