“Gout,” wrote the eminent 17th century physician Thomas Sydenham, “destroys more rich than poor persons, and more wise men than fools, which seems to demonstrate the justice and strict impartiality of Providence, who abundantly supplies those that want some of the conveniences of life with other advantages, and tempers its profusion to others with equal mixture of evil.”

Sydenham’s reflection on providential justice—the belief that gout afflicted primarily the wealthy and privileged classes of society—has long been a source of amusement to common people. Indeed, the morbus dominorum was widely taken as symbolic of a leisured class whose members brought their grief upon themselves through excessive living.

Physicians thought that gout (known by its official medical name Podagra) was caused by superfluous humors collecting in the joints. In fact, the disease is brought on by abnormally high concentrations of uric acid in the blood, causing deposits of uric salts to build up in the joints. Gout afflicts the joints of the extremities—classically the big toe. During attacks, which occur suddenly, often during the night, the joints become swollen and excruciatingly painful.

Early modern physicians knew that meat- and fat-rich diets contribute to the condition, which is why gout tended to afflict the upper classes. Thus the disease earned the nickname “patrician’s malady” from the belief that the wellborn and mighty brought the disease upon themselves through their profligate lifestyle.

Eighteenth-century literature abounds in caricatures of gouty aristocrats and merchants. Yet few such references survive from earlier periods. One of these is a delightful story told by the Puritan divine Richard Hawes in 1634.

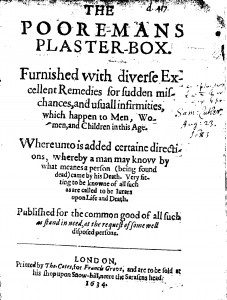

The story appears in Hawes’s The Poore-Mans Plaster-Box (London, 1634), a popular medical handbook that Hawes wrote for his parishioners. Hawes spent most of his ministry in Kentchurch, Herefordshire, a parish that the 19th century historian Edmund Calamy described as “a Paganish and brutish place”—which partly accounts for Hawes’s “limited success” there. But the fault lay just as likely with Hawes himself: “For many years after he entered into the ministry,” Calamy relates, the minister “continued much addicted to vain company, and was sometimes guilty of excessive drinking.” Hawes later amended his ways and, according to Calamy, “became a plain, earnest, and useful preacher.”

The story appears in Hawes’s The Poore-Mans Plaster-Box (London, 1634), a popular medical handbook that Hawes wrote for his parishioners. Hawes spent most of his ministry in Kentchurch, Herefordshire, a parish that the 19th century historian Edmund Calamy described as “a Paganish and brutish place”—which partly accounts for Hawes’s “limited success” there. But the fault lay just as likely with Hawes himself: “For many years after he entered into the ministry,” Calamy relates, the minister “continued much addicted to vain company, and was sometimes guilty of excessive drinking.” Hawes later amended his ways and, according to Calamy, “became a plain, earnest, and useful preacher.”

If Hawes’s success as a spiritual guide to his parish was imperfect, he performed an indispensable service as a lay physician. In rural communities, where professional medical assistance was limited, clergymen were often the only reliable medical practitioners. The Poore-Mans Plaster-Box bears the distinct mark of a man who had sound empirical knowledge of the medical problems of country folk. Most of the cures are for the ailments of working people: bruises, earache, nosebleed, burns, toothache, hemorrhoids, etc. Some of the treatments vividly portray the violent tenor of peasant life, including a prescription for “one that is beaten on the face that is black and blewe.”

On the other hand, Hawes gives no attention whatsoever to theoretical matters. He passes over the causes of diseases, for “they are written of at large in the sundry bookes of learned men: and are not to be understood of every meane capacity.” As for symptoms, “they are apparent enough.”

Believing that “a merry tale sometimes easeth paine,” Hawes recorded the following story, a parable explaining why gout “commonly keepes good company.” The reason, according to the tale, is the bad treatment it once received in a poor man’s house.

A tale that is true enough

A great while ago, when Monseiur Gout was not so rich (as now he is), he was forced to travel, as other poor men are sometimes. In his travel he met with a spider, whose journey lay as Mr. Gout’s did. They being both benighted, the sought lodging, and came to a poore man’s house, which the Gout took up for his lodging, for he being always a lazy companion, would go no further; but the spider being more nimble, went to a rich man’s house, and there took up his lodging for that night. The next day they met again, and asked eachotehr of their entertainment the past night.

“Mine,” said the Goud, “was the worst as ever I had, for I had no sooner touched the poor man’s legs, thinking there to take my rest, but up he gets, and to thrashing he goes, so that I had no rest the whole night.”

“And I,” said the spider, “had no sooner begun to build my house in the rich man’s chamber, but the maid came with a broom, and tore down all my work, and so fiercely did pursue me, that I had so much ado to save my life, as ever I had.”

“Seeing it is so,” said the Gout, “we will change lodging. I will go to the rich man’s house, and thou shalt go to the poor man’s.” They both were well content, and did so, and found such ease and rest in the lodging, that they resolved never to remove, for the spider built and was not troubled, the Gout he was entertained with a soft cushion, with down pillows, with dainty caudle, and delicate broths. In brief, he did like it so well, that ever since he takes up his lodging with rich men, where I desire that he should take his rest, rather that in my poor house.

One might ask: If the poor man is free of gout, why should Hawes mention it at all? “I doe it,” he explained, “for poore prodigals, who often spend their monies, yet keep this disease.”

References:

William Eamon, “The Tale of Monsieur Gout,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 55 (1981): 564-7 (from which this post is adapted).

Richard Hawes, The Poore-Mans Plaster-Box (London, 1634).

Roy Porter and G. S. Rousseau, Gout: The Patrician’s Malady. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000).