Continuing the theme of curiosity in the Renaissance that I began a couple of weeks ago with my post, “The Disease of Curiosity,” it makes sense to ask: What did it mean to be a curious person in the Renaissance? Which brings us to a quintessential but perhaps little known Renaissance figure: The Renaissance ‘curioso’.

The Renaissance curioso was a person, quite simply, who was interested in everything. Take, for example, the Spanish bibliophile and dilettante Vincencio Juan de Lastanosa, a minor nobleman who lived in the town of Huesca, in Aragon. Lastanosa, who lived in the 17th century, typified the Baroque curioso, hence the height of the tradition. A friend of the poet Gracián, he amassed a huge collection of books, coins, medals, and archeological artifacts, which filled his house in the center of the city and attracted visitors from all over Spain.

By identifying himself as a ‘curioso,’ Lastanosa meant something quite specific. He intended to situate himself within a community of individuals who made up a cosmopolitan elite that spanned national and confessional boundaries. Although leisure and wealth were important markers of the curioso’s status, more distinctive was a painstaking attention trained on the novel, rare, and unusual events and objects of nature. The community of the curious, who also described themselves as the ‘virtuosi,’ was diverse, embracing physicians, clergymen, apothecaries, lawyers and merchants; but it was united in its preoccupation with the marvels of art and the ‘secrets of nature.’ As Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park observe, “To count as one of the ‘curious’ was to combine a thirst to know with an appetite for marvels, which also came to be known as ‘curiosities’.” Collecting objects was deployed as a means of establishing one’s credentials as a member of this new elite – an elite of wealth, to be sure, but also one of taste and refinement.

Nothing was more characteristic of the curiosi than a passion for collecting. Thence emerged the Kunstkammern or cabinets of curiosities that were so characteristic of the baroque. The objects assembled in the curiosity cabinets resembled one another in blurring the boundary between art and nature and in playing on the ricochet between one form and another, underscoring the ambiguity of status between art and nature. Lastanosa’s collection boasted countless objects that would fall under the category of “rarities” or exotica. He owned, among other objects, exquisite stones used by American Indians as medical remedies; a shell in the shape of a boat (a Nautilus shell?) carved with “men, birds, and plants from China;” a sculpture of a black man’s head in jet; two Chinese chests with mother-of-pearl and gilt inlay; and three Mexican idols. He collected mathematical and optical instruments, maps, prints, paintings, tapestries, sculptures, and carvings.

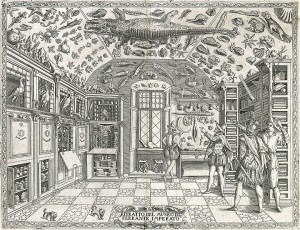

We don’t have any images from Lastanosa’ collection, but a similar “museum” owned by Ferrante Imperato of Naples is pictured here.

And what was the appropriate response to these cabinets, with their bewildering variety of variety? Wonder.

Historians have offered a number of different explanations for the sudden explosion of collecting in early modern Europe, in particular among the nobility. Some historians stress the importance of the commercial revolution and the growth of international trade, which made exotic naturalia and artificialia more readily available to collectors, whether through contacts with apothecaries or merchants. Others have emphasized the political importance of collections as expressions of dominion over nature and the world. Still others have linked collecting to the shifting fortunes of the nobility, arguing that the passion for collecting was a kind of pathology emanating from depression or melancholia, as the disease was then known. Robert Burton, whose Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) became the defining treatise on the subject, detected an “epidemic” of melancholy in his time, particularly among the middling and upper classes.

In the courtly culture that characterized the Renaissance, collecting was also related to the harnessing of wonder as a social and political asset. Objects deemed suitable for collecting were deliberately selected for their anomalousness – thus setting them apart from the ordinary. The juxtaposition of objects with strikingly different themes and aspects emphasized the unusual, novel, and rare. Like a display of wit, the exhibition of physical objects in collections and curiosity cabinets was designed to elicit wonder, both in regard to the objects and in regard to the collector of them.

Most early modern cabinets of curiosities seem, on the surface, to have repudiated any concept of order. Carved gems, watches, antiques, mummies, and mechanical contrivances are displayed alongside fossils, shells, skeletons, giants’ teeth, unicorns’ horns, and exotic specimens from the New World, making up an encyclopedia of the bizarre and the marvelous. They seem intended only to delight spectators and to provoke wonder rather than to serve as museums for research.

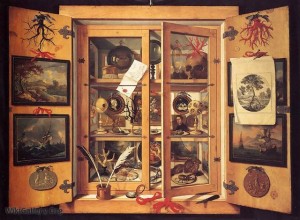

This 17th-century trompe-l’oeil painting of a cabinet of curiosities by Domenico Remps further blurs the boundary between nature and art, between real and fictitious spaces. (Domenico Remps, Cabinet of Curiosities, 1690s, Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Florence)

Yet, in fact, the bewildering variety of objects included in the collections, the deliberate blurring of the boundaries between art and nature, served to illustrate the baroque view that the multiformity of nature concealed a web of secret relations and forces: they are the ‘secrets of nature’ that natural philosophy was supposed to reveal.

Being a curious person in the Renaissance meant being interested in everything. Avaricious and undisciplined, Renaissance curiosity was nevertheless the engine of discovery and the beginning of modern science.

Curious readers can learn more about the Renaissance curioso from these works:

Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park, Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750. New York: Zone Books, 1998

Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994.

To learn more about Lastanosa, see the essays in The Gentleman, the Virtuoso, the Inquirer: Vincencio Juan de Lastanosa and the Art of Collecting in Early Modern Spain, ed. Mar Rey-Bueno and Miguel López-Pérez (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008). My essay from that volume, “Appearance, Artifice, and Reality: Collecting Secrets in Courtly Culture,” can be found here.

This is an excellent story. Did you think that its true ?