[Note: In the course of doing research, historians sometimes come across stories that seem to cry out to be told. Here’s one that I encountered in the Inquisition file in the Venetian State Archive a few years ago. It’s from Archivio di Stato, Venice, Sant’Uffizio, b. 23, containing the trial testimony of Antonio Vulpino, 9 April 1567. This blog is adapted from a longer article in which I try to interpret the documents. Here my aim is simply to tell the story.]

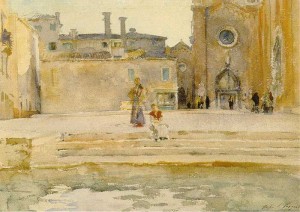

Campo San Lio, Venice, in a picture by Giovanni Mansueti depicting the Miracle of the Relic of the Holy Cross in Campo San Lio (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice)

On a cold January day in 1567, two men, one a Dominican friar called Antonio Volpe, the other a servant in the house of a local nobleman, were walking in the Campo San Lio not far from the Ponte Rialto in Venice. Pausing near a baker’s shop in the tiny square, they were suddenly approached by guards wearing the insignia of the Holy Office of the Inquisition. As the captain of the guards grasped Volpe’s arm, the friar turned to his companion and cried out, “I’m ruined (assassinato)! May God help me!” His friend, perhaps hoping to distance himself from the friar, responded, “Padre, if you’re a good man, God will help you; but should you be otherwise, so much the worse for you.”

Fra Volpe was quickly led to a boat docked nearby and conducted to the Holy Office’s prison at the church of San Giovanni in Bragora. A few days later he was transferred to the offices of the Inquisition in Padua, where the charges against him had been filed.There he learned the full details of the accusations against him: that secretly he was a Lutheran, that he owned heretical books, and that he was planning to throw off his habit and emigrate to Protestant Germany. Other charges would emerge in the course of the proceedings, which dragged out for another thirteen months as Volpe languished in the Inquisition’s prison while his case was being prosecuted.

Fra Volpe’s case was in many ways typical of those encountered in the archives of the Venetian Inquisition. Like most inquisitorial proceedings, his troubles began with a denunciation filed with the Holy Office. The fact that a capitano of the Holy Office was sent to arrest the friar suggests that the inquisitors thought that his case was particularly grave, or that they had reason to believe that he might flee; normally, when a decision was made to proceed with a case, the suspect was sent a citation to appear in court.

Volpe was a familiar figure around Venice. A native of Ferrandina, in Lucania, a poor region in the far south of Italy, he was a famous preacher whose sermons were said to have “moved people to tears of devotion.” But he was even more celebrated for the medicines that he made at a distillery in the Campo dei Frari and sold at the San Marco pharmacy. Most Venetians simply called him the “Canker Friar” (il frate del cancaro) because he had remedies for the sores caused by Mal francese, the French Disease—presumably syphilis—that were widely sought after and considered to be very effective. Fra Volpe’s clients—men and women alike—included patricians like Jacomo Badoer as well as countless poor people that he treated at the hospital at San Marco. People also consulted the friar for eye ailments and skin rashes. Rumor was that barbers and empirics would do almost anything to get hold of his secrets.

Volpe was a familiar figure around Venice. A native of Ferrandina, in Lucania, a poor region in the far south of Italy, he was a famous preacher whose sermons were said to have “moved people to tears of devotion.” But he was even more celebrated for the medicines that he made at a distillery in the Campo dei Frari and sold at the San Marco pharmacy. Most Venetians simply called him the “Canker Friar” (il frate del cancaro) because he had remedies for the sores caused by Mal francese, the French Disease—presumably syphilis—that were widely sought after and considered to be very effective. Fra Volpe’s clients—men and women alike—included patricians like Jacomo Badoer as well as countless poor people that he treated at the hospital at San Marco. People also consulted the friar for eye ailments and skin rashes. Rumor was that barbers and empirics would do almost anything to get hold of his secrets.

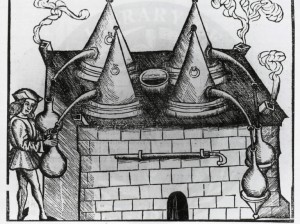

We don’t know much about Fra Volpe’s treatment for Mal francese, only that he made it in a distillery located in the Campo dei Frari. It is significant, however, that the friar’s small library contained only one medical book: Leonardo Fioravanti’s Capricci medicinali, which is devoted almost entirely to alchemical cures—that is, drugs made by distillation. When the Inquisitors interrogated Fioravanti, they learned that he had spoken to the friar “numerous times” about medical matters.

Given the friar’s fame, it’s not surprising that his troubles with the Inquisition were generally known among the circles of healers, distillers, and alchemists around Venice. The distillery in Campo dei Frari was a favorite meeting place of alchemists and empirics, who were always interested the latest concoction that might be brewing there. In densely populated Venice, where neighborhoods spilled over into one another and windows opened onto tiny courtyards, rumor and gossip were rampant. It was difficult to keep a secret in Venice. Gossip was useful to the Holy Office, too: It turned up suspects and made denunciations almost casual. As Volpe’s trial proceeded, rumor proved extremely damaging to his case.

Soon Volpe learned that his accuser was the physician Decio Bellobuono. Like Volpe, Decio was originally from the South. He had emigrated with his father, Prudentio, and his two brothers, Galeno and Propertio. After settling in Verona in the 1560s, the family moved to Padua, where Decio attended the university.

Suspicions about Volpe’s orthodoxy had actually surfaced earlier, however, in fact at least a month before his arrest, when the rumor began to spread that he had been decapitated in Naples as a Lutheran heretic. It was also rumored that he didn’t believe in the intercession of the saints, that he declared Saint Mary of Loreto to be the Pope’s whore, and that he proclaimed that Lutheran Germany was the promised land and the “Elysian fields.”

Other damaging testimony concerning Volpe’s personal life and religious orthodoxy emerged. There was a rumor that the friar wanted to throw off the habit and marry a woman from Padua by the name of Camilla; others testified that he said that the sins of the flesh were not so bad, “because man leans that way.” It was even rumored that he planned to leave Italy and go to a monastery in Austria, in a remote place called Terra Domini or Terra Santa, where “people lived in a saintly and plentiful manner.”

Decio Bellobuono counted on Venice’s lively gossip network in contriving his plot to frame Volpe. In fact, it turned out it was the Bellobuoni who were actually responsible for the rumors that got the friar in trouble the first place—or, at any rate, that’s what the rumors said. The summer before his arrest, the friar had gone to Puglia to make aqua vita, taking along with him Decio’s younger brother Propertio, who wanted to learn the art.

While there, Propertio met a rich widow and schemed to marry her for her property. Posing as a Venetian merchant awaiting a shipload of goods from Venice, he courted the widow and made promises to her, hoping that she would succumb to his solicitations. When Fra Volpe learned of the scheme, he went to the woman’s relatives and told them that Propertio was no rich merchant at all, but just a young wastrel seeking easy gain. His design on the widow ruined, Propertio returned to Venice and began spreading the rumor that the friar had been arrested in Naples and executed for heresy.

When Fra Volpe returned unexpectedly to Venice in January 1567, the rumors about his heretical religious beliefs, his supposed concubine, and his troubles in Naples were all well known around town. As the authorities began to probe more deeply into his case, however, other troubling information surfaced. Practically everyone who knew Volpe testified that when they heard about his denunciation, they suspected that it had to do with certain business transactions between him and Decio Bellobuono.

Distillation apparatus, probably similar to the one Fra Volpe used to manufacture his drugs (from Hieronymus Brunschvig)

The details are murky and the testimony is contradictory, but the substance of the affair can be made out with reasonable certainty. Fra Volpe’s drugs, which he manufactured at the distillery in the Campo dei Frari, brought him handsome profits. Soon he was lending money to various empirics and distillers around Venice. A few years before his trial, he loaned Decio Bellobuono 200 ducats so that Decio could purchase the distillery under his brother’s name, since it was illegal for physicians to own a pharmaceutical establishment.

When Volpe tried to collect the money owed him, Bellobuono refused to pay up, and when the friar threatened to take legal measures to collect the debt, Bellobuono denounced him to the Inquisition. But if the Bellobuoni could defame the Canker Friar to get out of paying their debt, it was a game that two could play; for Volpe knew a secret about the Bellobuoni and their unsavory past, and he was now prepared to reveal it.

Fra Volpe began to take charge of his case. He requested that other witnesses be examined and brought forth documents supporting his case. He charged the Bellobuoni of “seducing” false testimony and stirring up dissension among his congregation. When the inquisitors began looking into the counter-charges, they discovered that Decio himself had taken an unusual interest in Lutheranism, having pressed a confessed heretic for information about the doctrine. Was Decio’s curiosity about Protestantism aimed at making his charges against Volpe credible?

Then the Canker Friar broke his silence and revealed his secret about the Bellobuoni. Not only was the heresy charge a frame-up to avoid repaying the loan, he declared, but the entire Bellobuono family had been banished from Naples for their involvement in a robbery and murder. Decio’s real name, he asserted, was Jacomo da Campania. Convicted of treason and murder, he fled with his family and migrated to Venice, where they changed their name to “Bello e buono,” or “Fine and Good.” As the Inquisition began to probe more deeply into the family’s past, Decio marshaled several well-connected witnesses to testify on his behalf.

It’s clear from the trial testimony that Fra Volpe had enemies: Some of the witnesses were physicians, who had little good to say about empirics; others owed the friar money; and some were distillers who seemed eager to get back at Volpe for refusing to reveal his secret cure and to eliminate a competitor from the medical marketplace.

From his prison cell, Fra Volpe doggedly protested his innocence and repudiated one by one the accusations of the Bellobuoni. Refusing to give in to the Inquisition’s intimidations, he insisted on reviewing the trial testimony. In January 1568, he wrote an impassioned plea to the authorities proclaiming his innocence and refuting the accusations against him. The deposition laid out the details of the loan and Bellobuono’s refusal to repay it, and charged that Decio intimidated witnesses to make false testimony against him. Volpe insisted that he had always preached orthodox doctrine. He pointed out that while in prison he had converted two heretics. He denied owning heretical books, claiming that all he owned was a breviary, a psalter, and a copy of Fioravanti’s Medical Caprices, which he used in his practice.

Finally, in February 1568, evidently eager to bring the case to a close, the Inquisition abruptly dismissed the charges and set Volpe free. As much as anything, the friar had simply worn the Inquisition down.

Yet as far as Volpe was concerned, the case was not over. After his release from prison, he determined to get back at the Bellobuoni and clear his name. He requested that new witnesses be called and that former witnesses be reexamined in order to have his “honor and name restored.” He produced hard evidence to support his case, including letters of credit in Propertio’s name dating from 1565, when the transaction took place, as well as witnesses who confirmed his story about the loan to Decio.

The proceedings dragged on for another six months. Eventually the Paduan authorities lost patience. They had heard enough, and wanted to bring the affair to an end once and for all. In July, the Holy Office concluded its investigation, evidently without resolving the case in favor of either party.

Who gets the last word in this sordid tale of war waged by lies, rumor, blackmail, and false accusations?

Volpe, it appears. Although he vanishes from history after his trial, he lent his voice to another man in similar desperate circumstances. In July 1568, about the time the last witnesses were deposed in Fra Volpe’s appeal, the Holy Office opened a case against Francesco Annovazzo, a solicitor who practiced at the Rialto. Arrested in early August, Annovazzo had been denounced as a Lutheran, and spent the next eight months in jail defending himself against the charge.

At first glance, it seems that the Bellobuoni were up to their old tricks again; for, as Annovazzo’s trial testimony discloses, Decio and Galeno owed the notary money and refused to pay their debt. Did the Bellobuoni try to frame Annovazzo as they had framed the Canker Friar?

That at least is what Annovazzo claimed. To prove his case, he used a clever stratagem: He brought forth the record of Fra Volpe’s trial, with its squalid details of the Bellobuoni’s shady past, their lies and rumor-mongering, and their false denunciations. He hurled a litany of counter-charges, calling Decio, among other things, an assassin, a fugitive, a seducer, a buyer of false testimony, a spy, a liar, and a traitor. Just as he had framed Fra Volpe, Annovazzo charged, so he had falsely accused the notary in order to avoid paying his debt.

Decio, feeling the noose tightening around his neck, wrote an apologetic letter to Annovazzo, still in prison, explaining how “infinitely astounded” he was that the lawyer could make such accusation. “I’ve always held you in my soul and conscience to be a gentleman and a good Christian,” Bellobuono wrote. Though Annovazzo, under torture, was made to confess to having held Lutheran beliefs, his vigorous self-defense brought to light information that badly tarnished the reputation of Bellobuoni.

Nothing is heard about Fra Volpe after his unfortunate encounter with the Inquisition. Perhaps he did marry Donna Camilla, the widow rumored to be his concubine. Perhaps he left Venice and went to Austria. Maybe he did finally make it to that “Holy Land” where people live in common, saintly, and with goods aplenty. We shall probably never know. Like so many others, he disappears in the mist of the past.

And Decio? He contracted the plague during the epidemic of 1576 and died in the Lazaretto Nuovo. His son, Lelio, is heard in a pathetic plea to the Public Health Board to be allowed to recover his father’s meager goods.

[Note: This post is adapted from my article “The Canker Friar: Piety and Intrigue in an Era of New Diseases,” in Piety and Plague in Europe: From Antiquity to the Early Modern Period, ed. Franco Mormando and Thomas W. Worcester, (Kirksville, MO: Truman State University Press, 2007), 156-76, where full references may be found.]

The Italians called syphilis “mal francese” but the French called it “mal de Naples”. So there!