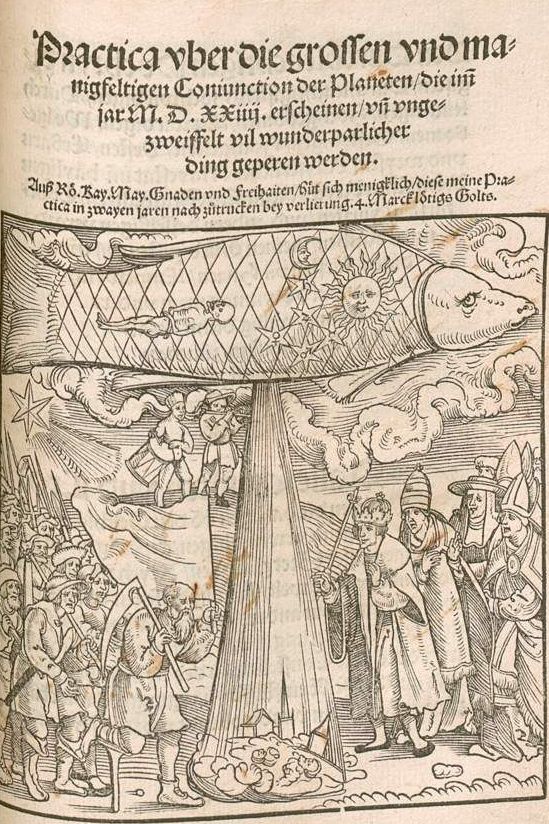

The biggest media event of the sixteenth century occurred in 1523-24, when scores of astrologers jumped onto a bandwagon of collective hysteria by proclaiming the imminent end of the world. The final days, the astrologers announced, would occur as a result of a second Deluge brought on by a conjunction of the three upper planets, Jupiter, Saturn, and Mars, in the sign of Pisces.

The great conjunction in Pisces, portending a second deluge. Leonhard Reinman, Practica uber die grossen und manigfeltigen Coniunction der Planeten (Nuremberg, 1524)

News of the prophecy spread quickly through sermons, broadsides, and almanacs. More than 160 works by 56 different authors weighed in on the dire prognostication, either by offering astrological evidence confirming the prophecy or denouncing it as a mad delusion. In January 1524 the Venetian chronicler Marin Sanudo reported that the mainland “is in great fear” over the impending catastrophe.

As intellectuals debated, people all over Europe frantically moved their places of residence in anticipation of the deluge. In Toulouse, a president of the parliament anxiously built an ark upon a mountaintop. Year by year as the dreaded date approached, apprehension increased and the prophecies grew more ominous. In a 1523 tract, the German astrologer Leonhard Reinmann predicted not only a great deluge but also a general uprising of peasants and common people. In Rome, general panic broke out.

Of course, the great flood never materialized. Torrential rains fell in some parts of Italy, but civilization was not swept away by the floods that ensued. Other parts of Europe remained dry. Yet the incident illustrates the extraordinary power that astrological prognostications held over intellectuals and common people alike.

The failure of this prophecy, upon which so many astrologers staked their professional careers, some scholars have argued, severely damaged the social authority of astrology. Some historians have suggested that the failure of the 1524 prophecy to materialize was one of the signal events determining astrology’s demise.

If that was the case, the end was a long time coming. Signs in the heavens continued to convey great significance down through the end of the seventeenth century. Astrology flourished in the Renaissance because it made sense to people and offered the power to predict the future, however imperfectly, in uncertain times.

The times were ripe for a groundswell of apocalyptic prophecies. The Black Death, famine, religious crisis, and political instability created a climate in which intense hopes and fears for the future took hold. The sense of historical crisis spawned innumerable predictions of the world’s end. By the time of the Great Schism (1378-1414), apocalyptic ideas were rife in Western Europe.

The Great Schism, when the papacy was divided between opposing “obediences” and two, then three rival popes claimed to lead the church, stirred up fervent expectations of the proximity of Antichrist’s reign. Countless apocalyptic visions and prophecies circulated. To many, the division of Christendom was a preamble to the advent of Antichrist.

Not everyone concurred. Initially Pierre d’Ailly, who was chancellor of the University of Paris from 1389 to 1395, agreed with those who saw the Schism as a sign of the approaching end of the world. But as the fissure widened, d’Ailly worried that the apocalyptic interpretation of the Schism served only to widen the rupture in the body of Christendom.

Turning to astrology for insights, D’Ailly, came to the conclusion that the return of the Antichrist would not occur until 1789, “if the world shall last that long.” Armed with this astrological knowledge, d’Ailly could refute the false prophets and visionaries, postpone the apocalypse to the distant future, and get on with the task at hand of healing the Schism.

While for d’Ailly astrology tempered the exuberant predictions of the apocalypse, others saw in the stars dire prophecies for Christendom. Despite the denunciations of astrology by Protestant reformers, including both Luther and Calvin, the sixteenth century was a veritable golden age of astrological prophecy. Indeed, Lutheran Germany was one of the hot spots of prophetic astrology.

The Reformation heightened society’s anticipation of the end of days. By making Scripture more generally accessible to readers, the reformers riveted the attention of believers on prophetic passages in the books of Daniel and Revelation, which they searched with ever-greater care for insights into the relationship between the present and the future

Johann Lichtenberger, one of Germany’s most prominent stargazers, churned out a string of prognostications in the 1470s and 1480s that continued to be published in German and Latin down through the sixteenth century. (Lichtenberger was most remembered for having predicted the German Peasants’ War of 1524-1525.) By 1600, some 60 editions of Lichtenberg’s Pronosticatio of 1488—one of ten astrological publications by him that survive—had been published.

Even Luther couldn’t stem the tide of Lichtenberger’s growing popularity: despite giving astrology a cold shoulder, he published a German edition of Lichtenberg’s prophecies in 1527, adding a preface spelling out his own position on the art. Luther denounced Lichtenberger as a false prophet intent on sowing confusion among rulers with his vague hints of future happenings.

In the second half of the sixteenth century, astrologers everywhere were pointing to signs in the skies that indicated deterioration and chaos so pronounced that it could only culminate in the end of the world. Tensions increased when, in 1572, a new star appeared in the heavens—the first since the star of Bethlehem announcing the birth of Christ. A few years later, in 1577, a bright comet blazed through the night sky, carrying all sorts of eschatological messages.

Soon astrologers were warning of another, far more ominous event looming on the horizon. In 1583, a rare conjunction of the superior planets Saturn and Jupiter would occur.

The reason why this conjunction was so menacing is that it was predicted to happen at the end of the “watery trigon” (comprised of the signs linked to water, Pisces, Cancer, and Scorpio), and at the beginning of the “fiery trigon,” the triplicity defined by the fiery signs of Aries, Leo, and Sagittarius. So exceptional was the fiery trigon conjunction that many astrologers connected it with an old prophecy for the year 1588 predicting major upheavals and the end of the world.

The European fascination with the Wonder Year of 1588 can be traced back to the supposed discovery among the papers of the German astronomer Regiomontanus (Johannes Müller) of a doggerel verse predicting great calamities for that year, which he was alleged to have scribbled on a leaf of paper.

Regiomontanus’s prediction was probably a fabrication, though this hardly seems to have mattered at the time. Once published in 1553, the prophecy was quickly endorsed by leading astrologers, including the Bohemian astronomer Cyprian Leowitz. In his De coniunctionibus magnis insignioribus superiorum planetarum (1564), Leowitz offered his interpretation of the conjunction’s significance: “Since . . . a new trigon, which is the fiery, is now imminent, undoubtedly new worlds will follow, which will be inaugurated by sudden and violent changes.” Leowitz went on to proclaim that the conjunction “undoubtedly announces the second coming of the son of God.”

The predicted fiery trigon conjunction spawned a huge body of prophetic literature, and the prophecies it generated were remembered long after the conjunction had come and gone. The message of the prophecies was clear, unmistakable, and always the same: The end is nigh; repent and do penance; turn to God while there was still time

As in 1524, the annus mirabilis came and went without calamitous results—much less the Second Coming. Astrologers, who had gone out on a limb predicting the end of the world, became the butt of ridicule. Philip Stubbes, in his Anatomy of Abuses (1583) chided the “foolish star tooters,” whose “presumptuous audacity and rash boldness . . . brought the world into such wonderful perplexity.” Henry Howard, Earl of Northampton, wrote that the astrologers should be shunned “like a dragon’s den.

Prophecies of doom traveled well in the sixteenth century, traversing both geographical borders and social class lines. In 1595, many of them were collected in a pamphlet published by the London printer Abel Jeffes titled A Most Strange and Wonderfull Prophesie upon this Troublesome World. In his pamphlet, which included some of the more sensational German prognostications updated for the times, Jeffes cobbled a multitude of heavenly portents, all meant to “move us to a penitent life that God may withhold his grievous scourge from us.”

According to some historians, astrology also fueled religious wars in France. Denis Crouzet, in his magisterial work, Les guerriers de Dieu, argues that an “intelligentsia of prophets” in sixteenth-century France created a “climate of anguish” among Catholics and encouraged them to implement Divine vengeance directly on the all-too-visible heretics around them. According to Crouzet, the extravagant rituals of violence and destruction that characterized the religious wars in France may be directly attributed to the “eschatological anguish” that resulted from the astrological prognostications.

The sixteenth century was an anxious age. Europeans trembled before the uncertainty surrounding death, the deterioration of social relationships, lingering questions about spiritual judgment, and the breakdown of the medieval cosmos, which had created an order seemingly rooted in the eternal principles of nature.

In the face of dissolving certainties, people turned to astrologers to find a pathway and guide to an indeterminate future. Whether it was to find a lost child, ascertain the most propitious moment take a journey, or determine the best time to start a business, astrology gave answers to questions that still vex humans. Even if the astrologer’s report was disappointing or grim, perhaps the news itself provided some relief and brought closure to nagging doubts.

While astrology might have given assurance in certain of life’s arenas, it also contributed to the anxieties of the time. Astrological prophecies of doom and the apocalypse may have been intended to encourage people to repent and prepare themselves for the end of days; but they cannot have provided much comfort in the face of the uncertainties surrounding their own life and death.

Ironically, astrology both confirmed the popular belief that humans are part of a larger whole and hence that their actions are not merely the result of chance or whim; and, at the same time, contributed to the heightened anxiety that would become a permanent feature of western culture.

Note: This post is adapted from my essay, “Astrology in Renaissance Society,” to be published in Astrology in the Renaissance, edited by Brendan Dooley (Brill).

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Margaret Aston, “The Fiery Trigon Conjunction: An Elizabethan Astrological Prediction.” Isis 61 (1970): 159-87.

Robin Bruce Barnes, Prophecy and Gnosis. Apocalypticism in the Wake of the Lutheran Reformation. Stanford, 1988.

William J. Bouwsma, “Anxiety and the Formation of Early Modern Culture,” in A Usable Past: Essays in European Cultural History (Berkeley, 1990), pp. 157-89.

Denis Crouzet, Les guerriers de Dieu : la violence au temps des troubles de religion, vers 1525-vers 1610. Seyssel: 2005.

C. Scott Dixon, “Popular Astrology and Lutheran Propaganda in Reformation Germany.” History 84 (1999): 403-18.

Anthony Grafton, Cardano’s Cosmos. The World and Works of a Renaissance Astrologer. Cambridge, MA, 1999.

D. Kurze, “Prophecy and History: Lichtenberger’s forecasts of events to come (from the fifteenth to the twentieth century); their reception and diffusion,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 21 (1958): 63-85.

Laura A. Smoller, History, Prophecy, and the Stars: The Christian Astrology of Pierre D’Ailly, 1350-1420 (Princeton, 1994).

Mr. Eamon,

One thing I’ve been wondering about is whether anyone in the Renaissance believed one could travel to other planets–that is, did anyone write about planets as either inhabited or inhabitable rather than as objects in the heavens that influenced individuals.

I would very much appreciate your reply and any direction you could give me as to sources. I’m not so much researching this as just curious.

Thanks for the question, Denise. Quite a few Renaissance astronomers and writers speculated about multiple worlds and even infinite universes, including Nicolas Cusanus and Giordano Bruno. Some even speculated about extraterrestrial life. Milton speculated about it in Paradise Lost, and there were other literary expressions of the idea. One famous text was by the 17th century English scientist John Wilkins, called Discovery of a World in the Moon. If you want to explore this further, I recommend Steven Dick’s book, Plurality of Worlds: The Extraterrestrial Life Debate from Democritus to Kant.