[Note: In my seminar on “The Scientific Revolution” this semester, I assigned graduate students to write a blog post that, once revised by the class during a workshop, I would publish on my “Labyrinth of Nature” blog. This is the second piece from that seminar, by Master’s anthropology student Enrique Reyes.]

When King Philip II of Spain moved his court to Madrid in the 1560s, making Madrid the capital of his kingdom, one of the deciding factors for his decision was the abundance of water. The word “Madrid” is derived from the Arabic word Mayra, which stands for water conduction; thus Madrid means place of mayras. Madrid’s qanāt system (in Spanish, “viajes de agua”) had been well established by the 1560s and Philip was well aware of this. Water was Spain’s lifeblood, as important in the Renaissance as it was during the Middle Ages.

The Moorish invasion in 711 A.D. of what was then known as Hispania introduced a myriad of Arabic influences. Among the most important were new technologies. In particular, a hydraulic technology known as a qanāt helped the Muslims establish themselves in the peninsula. From the end of Visigothic rule to the 17th century, the morisco and Christian populations propagated this technology for both rural and urban uses.

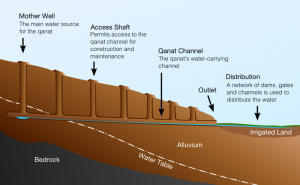

The qanāt originated in Iran around 2,000 B.C. and spread throughout the Middle East, into North Africa, and eventually into Spain with the Moors. A qanāt is a subterranean channel, or aqueduct, that tapped into the water table and, through a filtration process, collected water. The qanāt was used for both irrigation and urban water supply. This was especially true in the arid deserts of the Middle East and the equally dry regions of Spain.

In constructing a qanāt, a mother well was first dug to reach the water table. Then, workers would dig horizontally at a predetermined slope that would allow gravity to do the work of moving the water. As the workers dug horizontally, vertical shafts would be excavated at determined intervals.

The vertical shafts served two purposes: (1) to provide air for the workers below the surface, and (2) to allow for continued maintenance of the qanāt, such as clearing the horizontal tunnel of silt buildup. On the surface, a series of holes mark out the vertical shaft openings and also tracked the direction of the underground channel. These ingenious structures enabled the Moors, and later the Spanish, to provide water, without pumping, for agriculture and urban use despite long dry periods when there was no surface water available.

Cross-Section of a Qanat (From "Qanat & Badgir" http://kab3ey.wordpress.com/2010/11/16/qanat-badgir)

When King Philip decided to move his court from Toledo to Madrid in 1561, the city was a sleepy market town of 16,000. Within just two decades its population had more than tripled, and by the end of the century Madrid had more than 50,000 inhabitants. The development of the city’s infrastructure could not keep pace with its explosive growth. Visitors frequently complained about filthy streets and stinking latrines. Lamberto Wyts, a Dutch traveler in the 1570s, wrote, “I find the city of Madrid to be the filthiest in all of Spain. In all of the streets there are great servidores, as they call them, which are big urinals full of piss and shit that are emptied into the streets, giving off an unimaginable and vile stench.” Despite such complaints, courtiers and those who trailed after them flocked to the city. [Eamon, 267-8]

During the medieval and early modern periods, groundwater was Madrid’s sole water source. In order to avoid evaporation of water through conventional open ditches, also known as acequias, the qanāt proved extremely efficient. Moreover, the qanāt network in Madrid supplied its burgeoning population with a growing demand for water and enabled the city to maintain for its inhabitants, however tenuously, a relatively efficient sanitary infrastructure.

Two existing qanāts in Madrid can trace their roots back to the medieval period. One is Los Caños Viejos, which transported water near the modern church of San Pedro and it was used for watering farmland and public baths. The other qanāt is the Caños del Peral, which originated outside the city walls and possibly dates to the Islamic Period. During excavations the basement of a wall tower was unearthed. Archaeologists speculate that it could have been a location to supervise the qanāt system, but it also could have served as a place of protection for the citizenry to collect water. [Segura-Graiño]

It was upon such novelties that both Muslim and Christian civilization in much of Iberia would be sustained.

By Enrique Rey (MA candidate, anthropology)

References:

William Eamon. The Professor of Secrets: Mystery, Medicine, and Alchemy in Renaissance Italy (Washington: National Geographic Books, 2010).

Paul Ward English. “Qanats and Lifeworlds in Iranian Plateau Villages,” Middle Eastern Natural Environments (1998)188-205.

Cristina Segura Graiño, “The Building of the Hydraulic System in Madrid (Spain) in the Middle Ages,” Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Construction History (Cottbus, 2009). [online]

Glick, Thomas F. Irrigation and Hydraulic Technology: Medieval Spain and its Legacy, (Variorum, 1996).