In addition to writing books for a general readership, I continue to be an active research scholar. I publish scholarly articles relating to various aspects of the history of Renaissance science and medicine. I have a particular interest in the history of science in the Mediterranean region and the Atlantic world. Occasionally, I will be talking about this research on my blog.

Here are some of my recently published articles, along with links to the articles:

“The Black Legend and the History of Early Modern Spanish Science,” Colorado Review of Hispanic Studies 7 (2010).

Why has Spain been largely left out of our histories of early modern science? This article explores some questions relating to the pervasive influence of the Black Legend on interpretations of Spain’s role in the Scientific Revolution. (On-line version available here.)

“Appearance, Artifice, and Reality: Collecting Secrets in Courtly Culture,” in The Gentleman, the Virtuoso, the Inquirer: Vincencio Juan de Lastanosa and the Art of Collecting in Early Modern Spain, ed. Mar Rey-Bueno and Miguel López-Pérez (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008).

Originally written for a conference on the provincial Spanish aristocrat and collector Vincencio Juan de Lastanosa, this article discusses Lastanosa’s activities as a collector of “secrets.” [Appearance, Artifice, Reality]

“Masters of Fire: Italian Alchemists in the Court of Philip II,” in Chymia: Science and Nature in Early Modern Europe (1450-1750), ed. Miguel López Pérez and Didier Kahn (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010), 138-56.

Originally written for a conference on alchemy in early modern Spain, this article looks at Philip II’s reliance on foreign expertise, and focuses on the experiences in the Spanish court of the Italian ‘professor of secrets’ Leonardo Fioravanti. (Link here).

“Cannibalism and Contagion: Framing Syphilis in Counter-Reformation Italy,” Early Science and Medicine 3 (1998): 1-31

The outbreak of syphilis in Europe elicited a variety of responses relating to the disease’s orgin and cure. In this essay, I examine the theory of the origins of syphilis advanced by the 16th-century surgeon Leonardo Fioravanti. According to Fioravanti, syphilis was not a new disease but had always existed, only recently breaking out in epidemic form. The epidemic, he argued, was caused by cannibalism among the French and Italian armies during the siege of Naples in 1494. Fioravanti’s strange and novel theory was connected with his view of disease as corruption of the body. His theory of bodily pollution, a metaphor of the corruption of society, coincided with Counter-Reformation concepts about sin and social order. (Cannibalism and Contagion).

“Physicians and the Reform of Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe,” Acta Histriae 17 (2009): 1-11.

The ancient rivalry between the learned physician and the unofficial, popular healer seems to have broken out with particular vindictiveness during the early modern period. Emboldened by a rapidly changing and increasingly competitive medical marketplace, charlatans and popular healers challenged traditional medicine in printed tracts and in public performances in the piazzas and marketplaces. The university-trained physicians responded to the challenge with a barrage of attacks on “popular errors.” The “errors of the people” in medicine became emblematic of the credulity and backwardness of popular culture in general. This paper, originally presented at a conference in Koper, Slovenia, focuses upon physicians’ writings on “popular errors” written between the mid-16th century and the early 18th century and analyzes the cultural codes and stereotypes about popular culture that emerged from these writings. (Link)

“Plebs amat empirica: Nicholas of Poland and His Critique of the Medieval Medical Establishment,” Sudhoffs Archiv 71 (1987): 180-96

This article, first published in 1987, is about the 13th-century Dominican friar and popular healer Nicholas of Poland, whose “alternative medical system” was based on the premise that God had implanted the most marvelous medical virtues in the humblest beings. Urging a return to “natural” methods of healing, he attributed extraordinary virtues to toads, scorpions, snakes, and lizards. He was also the author of a fierce invective against the medical establishment. This article was the basis of my blog post, “The Monk Who Loved to Eat Toads.” (Link to article).

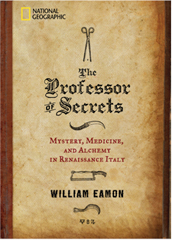

SET AGAINST THE SUMPTUOUS BACKDROP

of Renaissance Italy, this riveting tale explores the era’s medicine and culture through the life of the world’s first "celebrity doctor"—whose miracle cures and outsize personality drew both adoration and scorn.

The Professor of Secrets was Leonardo Fioravanti, a brilliant, forward-thinking, and utterly unconventional doctor... His marvelous remedies and talent for self-aggrandizement earned him the adoration of the people, the derision of the medical establishment, and a reputation as one of his era’s most colorful and combative figures.

SET AGAINST THE SUMPTUOUS BACKDROP

of Renaissance Italy, this riveting tale explores the era’s medicine and culture through the life of the world’s first "celebrity doctor"—whose miracle cures and outsize personality drew both adoration and scorn.

The Professor of Secrets was Leonardo Fioravanti, a brilliant, forward-thinking, and utterly unconventional doctor... His marvelous remedies and talent for self-aggrandizement earned him the adoration of the people, the derision of the medical establishment, and a reputation as one of his era’s most colorful and combative figures.