Fourteen hundred ninety-two has gone down in history as Spain’s annus mirabilis—and the year the modern world began. The year commenced, appropriately enough, with great fanfare in a field outside the fabled city of Granada. Its main characters were King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile, who by marriage had united Spain’s two greatest kingdoms and by warfare had retaken the lands held for 5 centuries by the Muslims.

For more than a decade the Catholic Monarchs had waged relentless warfare in their attempt to expel the Moors, as they called the Muslims, from Andalusia. By 1490, they had closed in on Granada, the last Moorish stronghold in Spain. The war, though seen as a necessary crusade, had taken its toll on the monarchs’ subjects, who were obliged to pay heavy taxes to support the effort.

Finally, on the 2nd of January 1492, in a solemn ceremony in an open field outside the walls of Granada, with the Alhambra glistening golden in the sunlit background, the last Nasrid ruler of al-Andalus, Mohammed XII, also known as Boabdil and to the Spanish as “El Chico,” handed over the keys to the palace to King Ferdinand, who passed them to the Queen. A chronicler reported that as the Moorish king placed the keys in Ferdinand’s hands, he said, “God must love you well, for these are the keys to his paradise.”

The Surrender of Granada, by Francisco Pradilla y Ortiz (1882). In this purely fictional portrayal, Boabdil appears before Ferdinand and Isabella and hands the keys to the Alhambra to King Ferdinand.

Witnessing the splendid pageant was a 14-year-old mozo de cámara (page) in the service of the Infante, Juan, the Catholic Monarchs’ only son and heir to the throne. The boy, Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo, was the scion of a distinguished Asturian family that had settled in Madrid. He would serve the monarchy in one capacity or another his entire life.

Also present at the ceremony was the Genoese adventurer Christopher Columbus, who had come to Granada not to take part in the siege but to present Queen Isabella, for the third time, his proposed “Enterprise of the Indies,” a daring—court cosmologists said preposterous—plan to reach Asia by sailing west. By finding a western route to the Indies—meaning Asia—Columbus claimed, he would circumvent the Ottoman blockade of the rich Asian spice trade that Europeans had enjoyed before the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

Years later, Oviedo remembered the events in the field near Granada. He like other contemporaries had no doubt that the defeat of the Moors after 500 years of rule in the Iberian Peninsula was the greatest achievement of the Catholic Monarchs’ reign. The victory, according to a chronicler in the Basque country, “redeemed Spain, indeed all Europe.” The surrender of Granada signified that Spain’s moment in history had arrived.

In the fullness of time, historians would conclude that the greatest achievement of the Catholic Monarchs’ reign was not the victory at Granada but the discovery and colonization of America. But this was hardly apparent on that January day in 1492. In fact, despite the fanfare that celebrated the victory, Columbus had no better luck on this occasion than he had the two previous times he offered his proposal to Queen Isabella.

Perhaps it was the enormous package of emoluments that Columbus demanded, including a knighthood, a coat of arms, and substantial revenues; or, possibly, it was the doubts cast on his project by the board of experts assembled to evaluate the proposal. Certainly Columbus’s estimate of the distance of the westward voyage to Asia was far less than current scholarly wisdom—or, for that matter, modern calculations—allowed. Whatever it was that gave the queen pause, Columbus’s proposal was turned down again.

It was only through the intervention of friends at court that Isabella reconsidered. Columbus, who had given up hope on Spain and was already on his way to France to present his idea to King Charles VIII, made it only ten miles before he was overtaken by a messenger and given orders to return to Santa Fe, the town near Granada where the court was then residing. This time, the monarchs—possibly worried over the loss of African gold tribute the Moors had traditionally paid and seeking other sources of the precious metal—agreed to finance the enterprise.

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, Prince Juan’s young page, was there to witness the ensuing negotiations between Columbus and the Catholic Monarchs, which resulted in the so-called “Capitulations of Santa Fe,” the Articles of Agreement naming Columbus Admiral of the Ocean Sea and viceroy over all the lands that he might discover. The monarchs also provided Columbus with letters of introduction to the Great Khan of Cathay, just in case.

Oviedo was also present at Barcelona in April 1493, when the Great Discoverer returned triumphantly to Spain after his first voyage to the New World and was led into the court along with a flock of iridescent, cackling parrots, specimens of medicinal plants, and 7 frightened Taino captives—“the first Indians of the discovery,” Oviedo matter-of-factly recounted. “I do not speak from hearsay of any of these events,” he wrote, “but as an eyewitness.”

Oviedo never forgot having seen Columbus in the Catholic Monarchs’ court—once as a humble supplicant, then as the most famous man in Spain. Nor, it seems, did he never cease dreaming of the possibility of visiting the New World himself. In 1514, at the age of 36, he finally got his chance. As the newly appointed supervisor of mines and smelting gold in Tierra Firme (now part of Central America), he joined the expedition of Pedrarias Dávila, which embarked from Seville with fifteen hundred men.

Oviedo lived a total of 27 years in the New World, most of them in Santo Domingo. He made 12 crossings back and forth from Spain to the Indies, both as mine supervisor and, later, as the official royal chronicler of the Indies. By the time of his death in 1557, he was a representative of an entirely new personality: a citizen of both the Old the New Worlds.

An indefatigable collector and shrewd observer, Oviedo meticulously recorded his impressions of the plants, animals, mines, and indigenous ways that he observed in the New World. He was an ethnologist, a geologist, a climatologist, and natural historian; and he piled up thousands of pages of notes on natural history and Native American culture.

Oviedo first wrote of his New World experiences in the form of a report to Charles I (later Holy Roman Emperor Charles V), Ferdinand’s grandson, who succeeded the Catholic King after the latter’s death in 1517 (Isabella died in 1504). Printed in 1526 under the title De la natural hystoria de las Indias (Natural History of the Indies), the book was widely read in Spanish as well as in English, French, and Italian translations. It was through Oviedo’s book that Europeans first learned about the hammock, which henceforth was adopted as the bed of choice by seamen throughout the world, and about avocados, pineapples, papayas, tobacco, and hundreds of other plants and animals used and hunted by the Native Americans.

De la natural hystoria de las Indias, better known as the Sumario, or Summary, was but a précis of the great treatise that Oviedo would later publish under the title Historia general y natural de las Indias (General and Natural History of the New World). The result of more than 20 years of recording data, the massive work was printed in Seville in 1535. Oviedo returned to Spain to personally oversee its publication.

The General and Natural History—the first comprehensive descriptive history of the New World—was fully 50 books long in manuscript, although the 1535 printed edition included only the first 19, which were dedicated to Columbus’s voyages and the Caribbean islands. The 20th book was published in 1557. The remainder—contained in a 2,000-page manuscript known today as the Monserrat manuscript after the monastery in whose care Oviedo left it—was not published until the 19th century.

Like all Renaissance writers on natural history, Oviedo was profoundly influenced by the ancient Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder. Yet, although Oviedo admired Pliny and mined his Natural History extensively, he was hardly a slavish follower of the ancient naturalist. In fact, while using Pliny’s work as a literary model, Oviedo self-consciously distanced himself from Pliny’s methods, writing that he had not simply “culled [his experiences] from two hundred thousand volumes,” as Pliny did:

I, however, compiled what I here write from two hundred thousand hardships, privations, and dangers in the more than twenty-two years that I have personally witnessed and experienced these things.

Oviedo’s independent attitude is everywhere apparent. Take, for example, his treatment of the jaguar, unknown in the Old World:

In my opinion these animals are not tigers, nor are they panthers or any of the numerous known animals that have spotted skins, nor some new animal that has a spotted skin and has not been described. The many animals that exist in the Indies that I describe here, or at least most of them, could not have been learned about from the ancients, since they exist in a land that had not been discovered until our own time. There is no mention made of these lands in Ptolemy’s Cosmography, nor in any other work, nor were they known until Christopher Columbus showed them to us.

Oviedo’s were the first reports about American natural history by a European who had actually been to the New World. Though some of the new world animals—such as foxes and deer—were similar to those seen in Spain, others were completely new. One can only imagine what Europeans thought when reading about such strange creatures as the armadillo, the anteater, or the sloth, which Oviedo judged to be “the stupidest animal in the world.”

Parrots—“better subjects for painters’ brushes than for words”—fascinated Oviedo. So worthy of royal attention did he find them that he brought back 30 specimens of 12 different species to present to King Ferdinand only a few weeks before the monarch’s death. Then there were these fascinating creatures:

There are some little birds so small that they are no larger than the end of the thumb. . . . Not only is this bird exceptionally small, but it is so swift in flight that it is as impossible to see its wings as it is those of a beetle or bumblebee. Everyone who sees it fly thinks it is a bumblebee.

The “bumblebee,” of course, was the hummingbird, an animal never before seen by Europeans. This quintessentially American creature would fascinate Europeans for centuries—as much as anything because it was always beyond their reach, restricted to the Americas and never successfully transplanted to Europe.

The longer Oviedo stayed in the New World, the less he relied on European formulas and schemas. Instead of describing things in terms of the familiar, he focused more on the particular. Because his subject was so out of the ordinary, he was forced to describe it on its own, peculiar terms. He insisted that only by being an “eyewitness” (un testigo) was he able to describe the marvels of the New World.

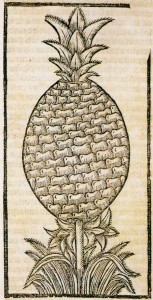

Increasingly Oviedo relied on visual images—though his own drawings were far from accomplished. Though simple and austere, they demonstrate that Oviedo took great pains to portray his subjects accurately. In drawing plants, for example, he tried to capture the generic characteristics of the plant rather that the features of any particular specimen, thus making identification in the field easier.

Oviedo’s treatment of the pineapple illustrates the predicament naturalists faced when attempting to name and describe new species. In certain respects, the plant resembles the artichoke; on the other hand, it also resembles a pinecone. So which is it? In fact, Oviedo concludes, it is neither, for the taste of its fruit is incomparable. “No other gives such contentment . . . there is no comparison between a good pineapple and any of the other fruits I have seen.” Oviedo acknowledges that he cannot adequately describe the plant in words; hence he must resort to a drawing—and even that could impart only a partial understanding.

Oviedo was the first European naturalist to confront what would become the perennial problem of the explorer-scientist: describing species and objects for which there were no familiar analogues. And there were thousands of completely new species to describe. As the Spanish explorers who followed Oviedo fanned out across Central and South America and sent back their reports to Spain, Europe’s scientific vocabulary, its pharmacopoeia, and even its cuisine changed dramatically. Words such as huracán (hurricane) entered the languages of Europe, and Europeans awakened to the realization of new and different peoples and cultures in distant lands.

There was also a darker side of the encounter that would eventually manifest itself: slavery, the inhuman treatment of the Indians, and new diseases—including syphilis, which Columbus’s crew brought back with his first voyage, and which quickly became an epidemic. It was not long before a New World cure for the disease was also discovered (according to the belief that God ordained that wherever a disease originates its cure should be found), in the form of guaiacán (Lignum Sanctum, the Holy Wood), which became a hot commodity, filling the coffers of the Fugger bank, which held a monopoly on its trade. After the New World encounter, everyday life in Europe would never be the same.

Gold panning scene from the Montserrat manuscript of Oviedo's Historia natural. Oviedo depicted numerous scenes from everyday life in America.

To Oviedo, it was the wondrous diversity of all things American that stood out the most. Addressing Charles V, he waxed enthusiastically about it:

What mortal understanding can comprehend such diversity of languages, habits, and customs among the people of the Indies? Such variety of animals, from domestic to wild and savage? Such an unutterable multitude of trees, some laden with diverse kinds of fruit and others barren, both those which the Indians cultivate and those produced by Nature’s own work without the aid of human hands? How many plants and herbs that are useful and beneficial to man? How many innumerable others unknown to him, whose flowers and sweet fragrances are so different from the ones he knows? . . . How many mountains more astonishing and frightening than Etna or Mongibel, Vulcan and Strogol, with one and all under your rule?

On and on he went in celebration of the Spanish conquest of America, which Oviedo thought was the most important accomplishment in history. And he was not modest about his own accomplishments. Future generations will be “awestruck,” he boasted, “that a single man could have written such a multitude of histories and secrets of nature.” Yet he was still being read with profit 3 centuries after his death. The great explorer-naturalist Alexander Von Humboldt admired Oviedo’s writings and considered him to be the founder of physical geography.

Though lauded in the 18th century by Von Humboldt, Oviedo is a largely forgotten figure when viewed from the perspective of the history of the Scientific Revolution. Sadly, the same can be said of almost all the Spanish naturalists and explorers who followed Oviedo in the 16th and 17th century. Such figures as José de Acosta, Nicolas Monardes, and Francisco Hernandez are barely mentioned in conventional histories of the Scientific Revolution.

That, unfortunately, is the case with Iberia in general. Spain’s absence from the “Grand Narrative” of the Scientific Revolution is puzzling. It is almost as if historians of the Scientific Revolution are living a dream world in which only Latin, English, French, Italian, and occasionally German is spoken.

Yet a world without Spain was certainly not the world that early modern Europeans thought they were living in. The Spanish Empire under the Hapsburgs reached from Madrid to Potosí and from Naples to Antwerp, not to mention the distant Philippines. The world’s first global empire, Spain produced the first worldwide scientific network—a fact that in the predominant interpretation of the history of science is met with stubborn ignorance or mute puzzlement. Remarkably, the situation today is not very different than it was when, in 1914, Julián Juderías coined the term “Black Legend” (leyenda negra) to describe the stereotype of early modern Spain as “Inquisitorial, ignorant, fanatical, incapable of taking a place among the cultured nations, always inclined toward violent repression, an enemy of progress and innovation.”

The Spanish and Portuguese confidently saw themselves as the first moderns surpassing the ancients. The English were the first to recognize this and to imitate the institutions the Iberians had created to gather scientific knowledge. Indeed, it was England, not Spain, which occupied the periphery in the 16th century. How it gained the center should be one of the leading questions about the Scientific Revolution.

Clearly, we need a new history of the Scientific Revolution—one that places Oviedo and the other Iberian explorers at the center, not the periphery.

REFERENCES

Antonio Barrera, Experiencing Nature: The Spanish American Empire and the Early Scientific Revolution (Austin, 2006)

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, “The Colonial Iberian Roots of the Scientific Revolution,” in Nature, Empire, and Nation: Explorations of the History of Science in the Iberian World (Standford, 2006), pp. 14-45

Antonello Gerbi, Nature in the New World: From Christopher Columbus to Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, trans. J. Moyle (Pittsburgh, 1985)

Kathleen Ann Myers, Fernandez de Oviedo’s Chronicle of America: A New History for a New World (Austin, 2007)

María Portuondo, Secret Science: Spanish Cosmography and the New World (Chicago, 2010)

This is the most beautifully written biography of Oviedo that I have come across. Thank you!